See also Lauren Husz’s post on How Did Statues Change from the Archaic to the Classical Period?

Introduction

Katerina Volioti, Lecturer in History at the University of Roehampton, has many years of experience in designing and delivering modules that blend in perspectives from Art History, the Social Sciences, and Digital Humanities. One of these modules, Art & Life in the Ancient World, has been particularly popular with international students in Spring Term 2024.

For their 2nd assignment, students had to complete a demanding task. They had to give a compact 7-minute presentation that addressed two complex questions about ancient and modern entanglements with objects in museum collections. This assessment was designed with a view to bypass the use of generative Artificial Intelligence. Students had to think outside the box to:

– envisage contexts of viewing and using artworks,

– evaluate museum online entries,

– reflect on pros and cons of Digital Humanities.

The assignment in full was as follows:

Select either an Etruscan or a Roman object from the collections of either the British Museum in London or the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Address the following questions:

1) How did people interact bodily with the object in ancient times?

2) How do people interact digitally with the object today?

It is with great pleasure to publish below work of a high academic standard by our Study Abroad student Rhianna Wallace. As you can see from Rhianna’s presentation, now adapted for the purpose of a blog, Rhianna navigates magnificently between the general and the specific, engages extremely well with relevant scholarship, assumes a comparative perspective in discussing collections, voices confidently her own views and observations from field trips, and brings together the two parts of the question. Over to Rhianna.

Rhianna Wallace

I am in my second year at Macquarie University, studying for a Bachelor’s in Ancient History. I have just completed a semester of exchange at the University of Roehampton, where I undertook Art and Life in the Ancient World by Dr Katerina Volioti. I have taken this opportunity to study overseas for the semester to immerse myself in a new place, travel Europe, and explore its many museums and archaeological sites so far from Australia! My following presentation originated as an assessment task I completed in the previously mentioned class and addresses one of the underlying themes. I was motivated to choose the topic of wall paintings for this task because I wanted to demonstrate the transparency of provenance and context museums such as the British Museum provide to their audience.

Acknowledgements

Rhianna Wallace: Professor Marciniak’s project looks incredible, and I am extremely grateful for including my work!

Katerina Volioti: We are, as always, most grateful to Professor Katarzyna Marciniak and the wonderful OMC Team for this fantastic opportunity to publish undergraduate student work. Professor Marciniak has repeatedly offered her time generously to talk and inspire our students at Roehampton about the reception and relevance of Classical Antiquity in the modern world. The idea of this blog post originated during Professor Marciniak’s talk on the Modern Argonauts ERC Project during Roehampton Employability Week in February 2024.

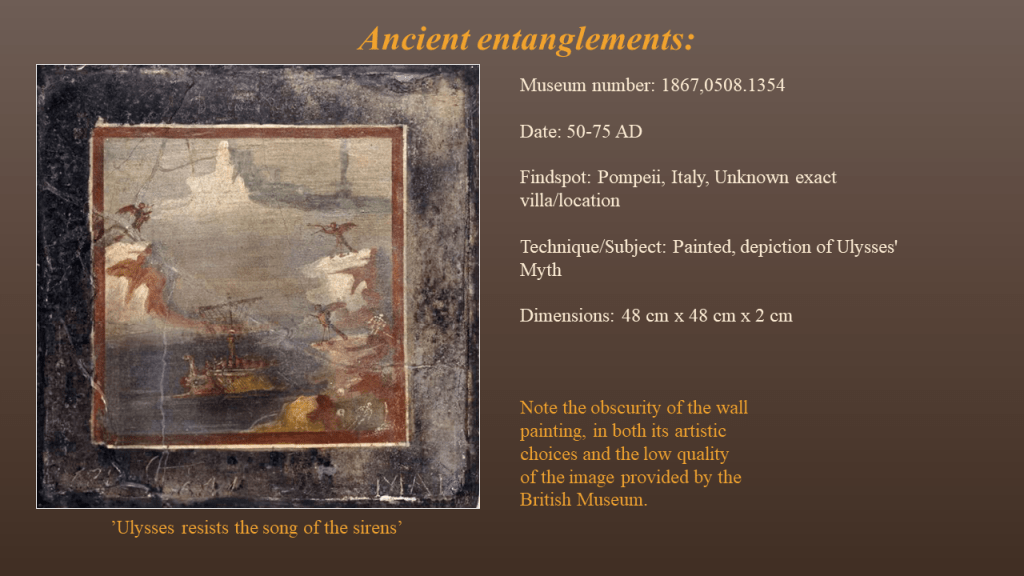

I will discuss the modern and ancient entanglements of the Roman wall painting, which portrays Ulysses resisting the song of the Sirens. The images used in the presentation are listed in the bibliographical section.

The painting is a mythological depiction of a popular Roman epic. Ian Hodder (Entangled: An Archaeology of the Relationships between Humans and Things, 2012) defines entanglement as a bodily engagement, not merely visual. Therefore, the wall painting’s pictorial narrative aids in encouraging interaction with its ancient audience.

Ancient Entanglements

This painting was once part of a wall in a Roman villa in Pompeii. It would have been displayed where it could entertain guests and the inhabitants of the villa. Moreover, due to its underlying moralistic allegory, it was also a tool of education and thus provoked interest and philosophical thought among viewers. For its ancient audience, the mythological scene would have conjured a sensory experience to transport them to a familiar, illusory world. They would have recognised representations of mysticism and felt the intended ambiguous sense of fear through the blurring depictions of mortal and immortal beings. They would have appreciated the animation of the scenery and the abstract atmosphere, which contributed to both the physical and the intangible entanglement.

Fabled characters such as Ulysses and his quests were common imagery exhibited in the domestic sphere, as they projected a narrative of Roman societal standards, as argued by Zahra Newby (Greek Myths in Roman Art and Culture: Imagery, Values and Identity in Italy, 50 BC–AD 250, 2016). Not only did an art-filled house exude wealth and status, but it also added to the pretence that the owners were highly educated and knowledgeable about Greek myth. It contributed to a program of otium. This Roman concept of leisure used luxury villas, emblematic of the elite lifestyle, to create a materialistic reflection of the inhabitants’ identities.

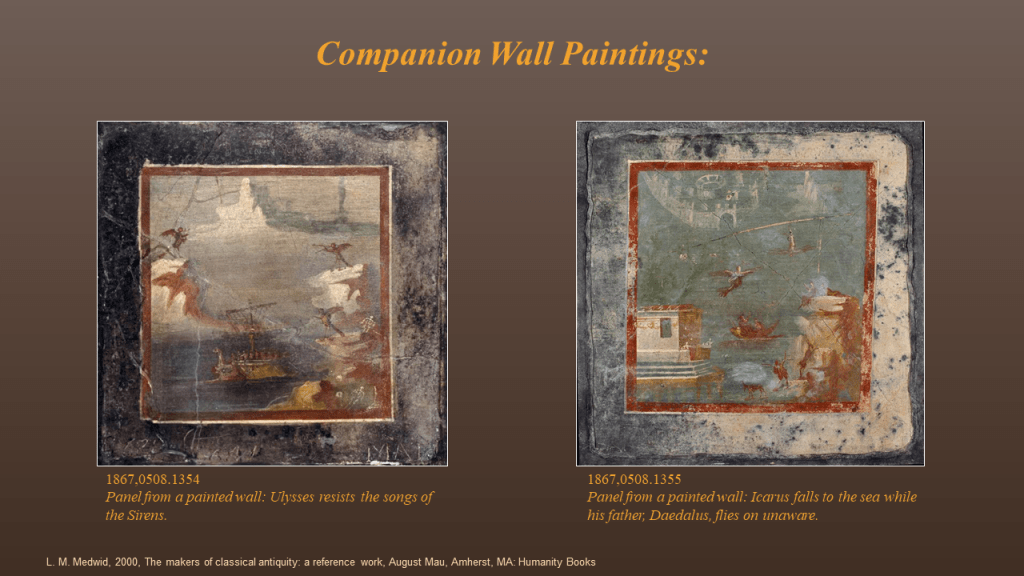

These two wall paintings are companions. From this depiction of Icarus and Dedalus, we can draw similarities, as both are representative of fictitious episodes. Due to the artist’s technique, we categorise these paintings as belonging to the third style of Roman wall painting, as defined by the German historian and archaeologist August Mau (1840–1909). Attributes of this style span whole walls within a house, incorporating stylised architecture to frame the mythological scenes housed within. We can also draw similarities in their functional and symbolic attributes that come together to communicate a message of morality in a warning against the dangers of temptation. Although they display differing scenes, the two paintings are both of mythological calibre and would have been extremely recognisable to Roman society and, hence, interacted with in everyday life.

Modern Entanglements

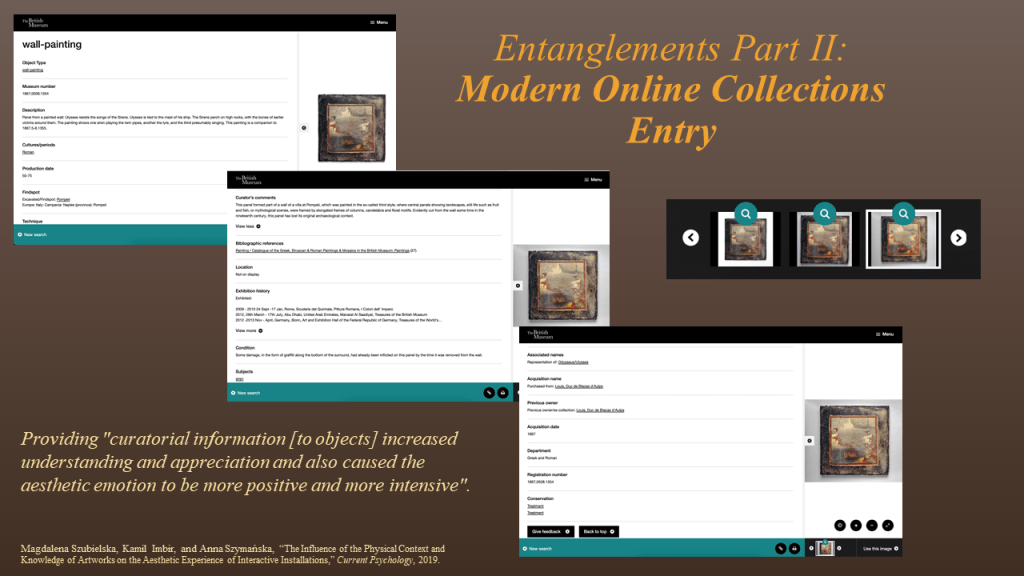

The wall painting is now owned by the British Museum. In its modern context, the object is not currently on display (see below, A Note from Warsaw); therefore, this online collection’s entry provides the only available information. It offers a clinical spotlight on the object; however, the page is not user-friendly and is cluttered. The harsh, contrasting stylistic choices interfere with the object’s limited view of the three low-quality images provided. It does not bridge the past to the present or provide the contextual background modern visitors require to guide their understanding.

The principal loss of the online entry is the sensory aspect that accompanies viewing the wall painting in both its ancient context and real life. Likewise, displays in a museum, where objects are behind glass, and you are not allowed to touch them (for the safety of the artefacts, of course), such as these other Pompeiian wall paintings, provide an artificially created context of overbright lights and fragmentary surrounding collections. As purely stand-alone art objects, they are stripped of their status as functioning objects of an ancient society. It disrupts the sensory connection and eliminates the ancient bodily interactions, the physical touch and the intangible immersion of sounds, sights, smells, and feelings that ancient connections would have endorsed. Evoking emotional connection through this sensory imagery fosters entanglement between the object and the observer, which is lost in current Roman Galleries displays.

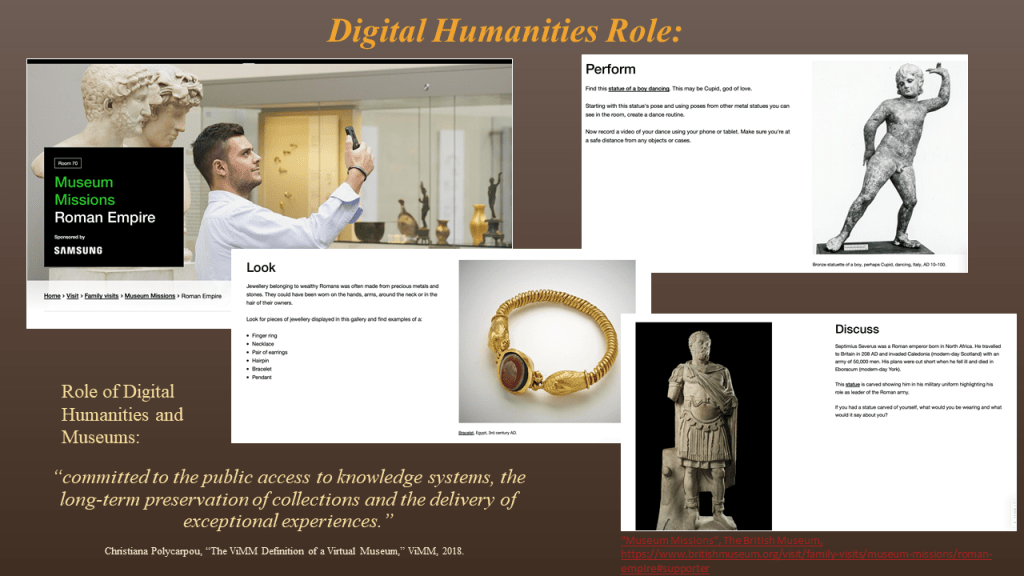

Lastly, I would like to touch on the unfortunate lack of innovation in modern entanglement that the British Museum is partaking in for this particular object. The British Museum markets itself as “the first national public museum of the world”. As technological advances and the digital humanities discipline grow, the Museum is obligated to devote resources to this sphere, or it risks failing to contend with other greater contributors, like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and losing touch with its audience.

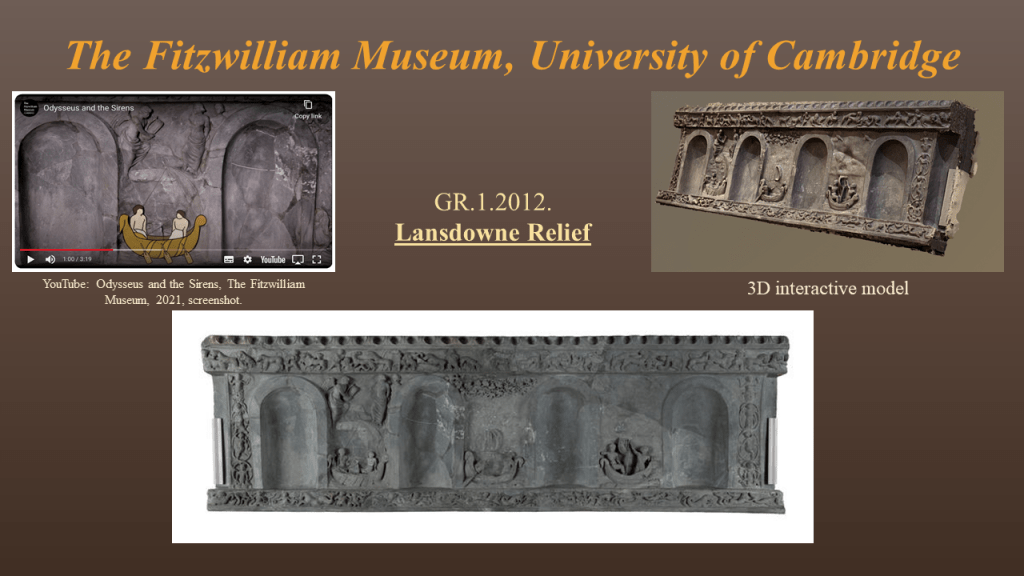

At the Fitzwilliam Museum at the University of Cambridge, the Lansdowne relief is a stone carving of the same story of Ulysses and the Sirens. The Fitzwilliam addresses the limitations of a stone relief to be lacking in entertainment due to its absence of colour. Instead, they take the opportunity to find value in encouraging the object’s digital humanities output. They do so by utilising the relief in an educational YouTube video, which not only gives the object a digital footprint but also broadens its exposure and visibility.

Currently, the British Museum has a broader digital humanities initiative for objects of the Roman Empire. The new engagement opportunity successfully encourages families to find objects, interact with them, and discuss with others. This initiative is a part of the Museum’s Mission, which fosters reflection, dialogue, and creativity, and ultimately allows for open interpretations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the entanglements of this wall painting, both ancient and modern, illuminate the dynamic interactions between humans and objects that transcend visual consumption. In its ancient context, the painting was a tool emblematic of Roman intellectual entertainment and was employed within a program of literary objects to represent status and wealth. Comparably, as a collection item of the British Museum, the fresco is treated as artwork that is primarily appreciated through vision. Ultimately, the juxtaposition of both ancient and modern entanglements highlights the significant interactions between object and audience.

Bibliography

All links were active on 6 July 2024

Archer, William C., “The Paintings in the Alae of the Casa Dei Vettii and a Definition of the Fourth Pompeian Style”, American Journal of Archaeology 94.1 (1990), 95–123, https://doi.org/10.2307/505527.

British Museum, “Wall-Painting | British Museum”, http://www.britishmuseum.org, n.d., https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1867-0508-1354.

Bruder, Kurt A., and Ozum Ucok, “Interactive Art Interpretation: How Viewers Make Sense of Paintings in Conversation”, Symbolic Interaction 23.4 (2000), 337–358, https://doi.org/10.1525/si.2000.23.4.337.

Cameron, Alan, Greek Mythography in the Roman World, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Damico, Anthony, Otium: Roman Views on the Proper Use of Leisure, Order No. 6611472, University of Cincinnati, 1966, https://roe.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/otium-roman-views-on-proper-use-leisure/docview/302346161/se-2.

Federici, Angelica, and Joseph Chandler Williams, Digital Humanities for Academic and Curatorial Practice”, Studies in Digital Heritage 3.2 (2020), 117–21, https://doi.org/10.14434/sdh.v3i2.27718.

Fitzwilliam Museum, “Lansdowne Relief”, 2024, https://collection.beta.fitz.ms/id/object/160187.

Fitzwilliam Museum, “Odysseus and the Sirens”, YouTube, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8E8EhD70gDE.

Hodder, Ian, Entangled: An Archaeology of the Relationships between Humans and Things, Maldan, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012, https://www.ian-hodder.com/books/entangled-an-archaeology-of-the-relationships-between-humans-and-things.

Newby, Zahra, Greek Myths in Roman Art and Culture: Imagery, Values and Identity in Italy, 50 BC–AD 250, Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139680387.

Olivito, Riccardo, M. Zarmakoupi, Designing for Luxury on the Bay of Naples: Villas and Landscapes (c. 100 BCE–79 CE), “Oxford Studies in Ancient Culture and Representation”, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Polycarpou, Christiana, “The ViMM Definition of a Virtual Museum”, ViMM, January 10, 2018, https://www.vi-mm.eu/2018/01/10/the-vimm-definition-of-a-virtual-museum.

Szubielska, Magdalena, Kamil Imbir, and Anna Szymańska, “The Influence of the Physical Context and Knowledge of Artworks on the Aesthetic Experience of Interactive Installations”, Current Psychology, June 15, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00322-w.

Theobald, William F., Global Tourism. Abingdon, Oxon–New York, NY: Routledge, 2016.

Khan Academy, Dr Steven Zucker, and Dr Beth Harris, “Scenes from Homer’s Odyssey, Via Graziosa”, in Smarthistory, 2023, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/roman/wall-painting/v/scenes-from-homers-odyssey-via-graziosa.

Images used in the presentation

- Google Maps: Roman Galleries, The British Museum, 2024, screenshot, https://artsandculture.google.com/streetview/british-museum/AwEp68JO4NECkQ?sv_h=0&sv_p=0&sv_pid=82msigh8dhOuggxoZyfOCQ&sv_lid=3582009757710443819&sv_lng=-0.1273865042017803&sv_lat=51.51901691357446&sv_z=0.6158686808497834.

- Matthias Kabel, phot., Villa of Mysteries, 2012, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Villa_of_Mysteries_(Pompeii)-19.jpg.

- Oliver Bonjoch, phot., Bay of Campania, 2010, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Baia_da_Villa_Schiano_Di_Pepe.jpg.

- The Metropolitan Museum, Cubiculum (bedroom) from the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale, 2017, The Metropolitan Museum – The Collection, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/247017.

- Unknown, phot., House of Julia Felix, 2019, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:House_of_Julia_Felix,_Pompeii_-_48000625962.jpg.

- Unknown, phot., House of Julia Felix, 2019, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:House_of_Julia_Felix,_Pompeii_-_48000627548.jpg.

Post by Rhianna Wallace, placed by Olga Strycharczyk

A Note from Warsaw (by Professor Katarzyna Marciniak)

Interestingly enough, when Rhianna Wallace, a student from the Macquarie University in Australia, was working on this paper for the module by Dr Katerina Volioti at the University of Roehampton in London, the fresco Ulysses Resists the Song of the Sirens was at display at the excellent exhibition curated by Dr Mikołaj Baliszewski, The Awakened. The Ruins of Antiquity and the Birth of the Italian Renaissance in the Royal Castle in Warsaw.

Photos by Katarzyna Marciniak.

Some taste of the immersive character of this exhibition is offered by this clip:

This exhibition is also a wonderful example of a cooperation between the museums from various parts of the world, incl. The British Museum, that are ready to share their treasures in order to make it possible for the viewers from other countries to engage with the ancient world. While the museum curators work intensively on developing new approaches and techniques in displaying the artefacts, one aspect does not change and may it never change! – the community spirit and the sense of mission in giving us all, as much as possible, access to the world cultural heritage. (KM)

3 thoughts on “Ancient and Modern Entanglements: Roman Wall Paintings, by Rhianna Wallace”