We are delighted to celebrate the publication of Teaching Ancient Greece: Lesson Plans, Animations, and Resources, the most recent result of the European Research Council (ERC) Consolidator Grant project Our Mythical Childhood… The Reception of Classical Antiquity in Children’s and Young Adults’ Culture in Response to Regional and Global Challenges. Teachers and other educators will find this open access volume a treasure trove of material for teaching and learning about ancient world topics, from pottery itself, through sacrifice, music, museums, poetry, drama, marriage, hunting, war and more.

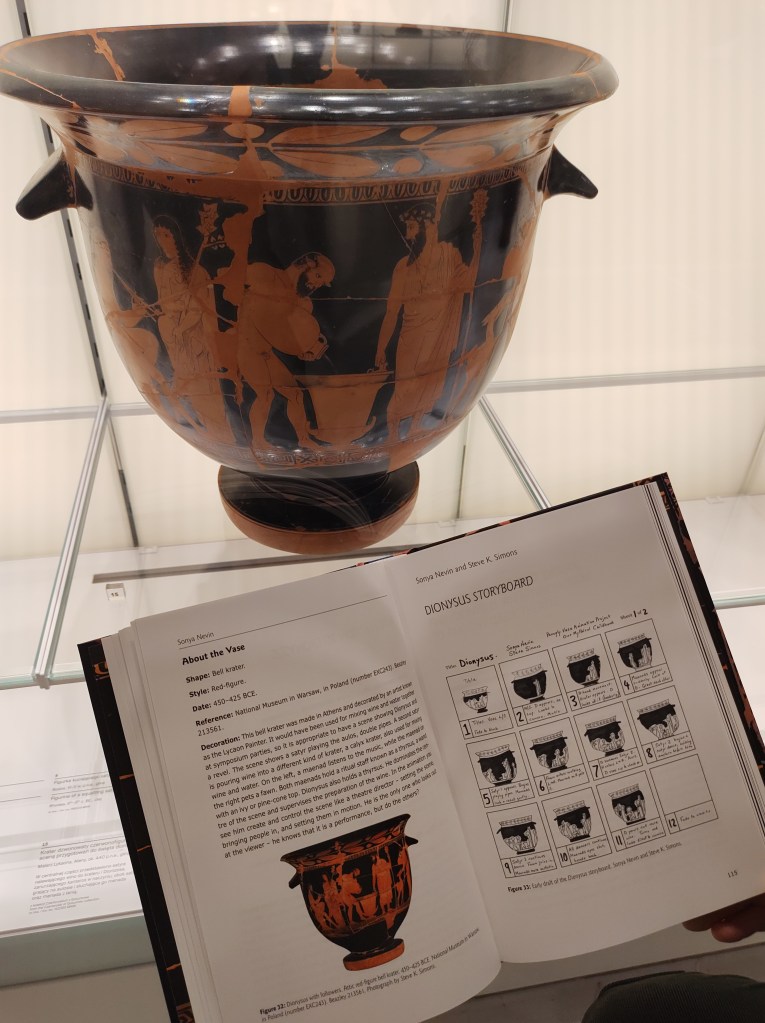

Teaching Ancient Greece was edited by Sonya Nevin, Assistant Professor at the University of Warsaw’s Faculty of “Artes Liberaes”. Dr Nevin works with animator Steve K. Simons on the Panoply Vase Animation Project, making short educational animations from real ancient artefacts. Where an ancient amphora shows the hero Heracles holding a boar, the animation shows him capturing it; where another vase shows the rainbow goddess Iris, the animation shows her flying, leaving rainbows streaking behind her. Five vase animations and four short documentaries were created for the Our Mythical Childhood project. They are based on five Greek vases from the collection of the National Museum in Warsaw. Now the animations and documentaries have been joined by Teaching Ancient Greece which transforms watching into a multitude of activities.

Teaching Ancient Greece contains activity sheets, including ones for learning the Greek alphabet, matching gods to their symbols, and for colouring in vases and creating new vase designs. These are joined by a set of ready-to-use lesson plans for teaching about the ancient world. Created by experienced educators all over the world, each lesson plan contains an introduction, a lesson including one of the animations, and an exciting activity to extend the learning experience. The target audience is secondary school pupils, but the lessons can all be adapted for older or younger groups.

Igor Cardoso in Brazil created a lesson about the poet Sappho, with writing activities about facing difficult situations. Ancient music specialist Aliki Markantonatou in Greece brings us a lesson on composing lyric poetry. This complements her recording of a unique version of one of Sappho’s poems, based on the music that the ancient poem would have been sung to. Ron Hancock-Jones in the UK used the Sappho animation to develop a lesson on marriage and relationships in ancient Greece. Chester Mbangchia in Cameroon created a lesson that introduces the god of drama, wine, and transformation – Dionysus. Theatre facilitator Olivia Gillman in the UK used the Dionysus animation as the basis for a drama class. Barbara Strycharczyk of “Strumienie” High School in Poland established a project for pupils in multiple years of the school who each worked towards an exhibition about the hero Heracles. Jessica Otto, in Germany, used the Heracles animation to show how stories can be represented and decoded through visual clues. Sonya Nevin offers several lessons on learning to “read” the images in Greek pottery, including one on the Libation animation, which shows the gods Zeus and Athena performing a libation sacrifice. Michael Stierstorfer in Germany used the same animation in a lesson about sacrifice in ancient Greece: what was done, how, and what it all meant. As for Iris, Dean Nevin in Switzerland brings us a writing challenge – messages for the rainbow messenger goddess to carry. Terri Kay Brown in New Zealand (Aotearoa) created an introduction to anthropology – a chance to compare different cultures’ myths about the rainbow and to consider what is indicated by the differences and similarities between them.

Other lessons explore the world of museums themselves. Museum educator Jennie Thornber in the UK offers a lesson for exploring museums in person or online and taking on the role of a curator. A PowerPoint on the Panoply site is one of several providing extra support for these activities. Louise Maguire in Ireland set an alternative curator’s challenge, asking learners to consider factors such as planning, budget, and accessibility in planning exhibitions.

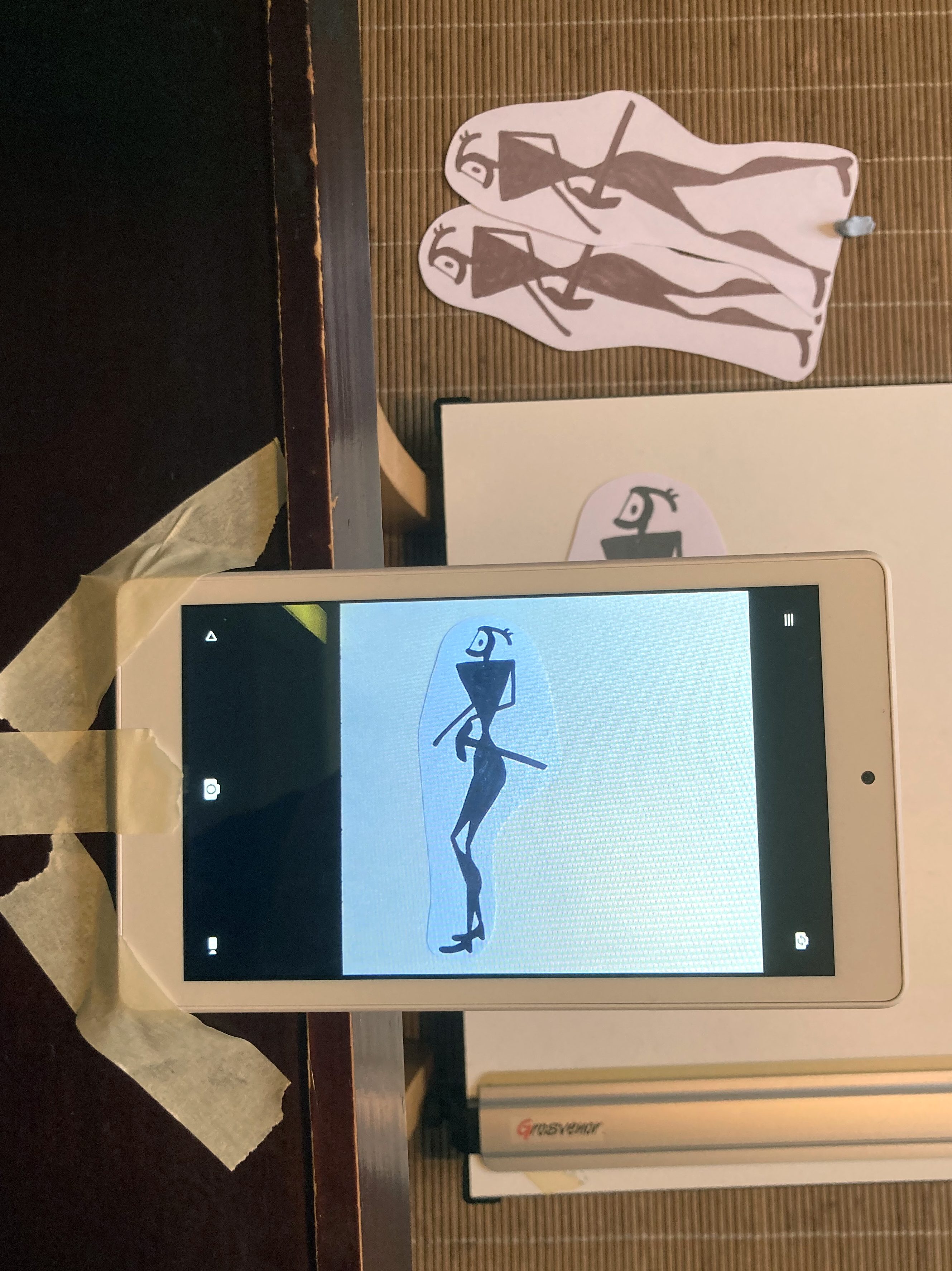

Perhaps all this talk of animation makes you feel like having a go at making your own stop-motion animation. Christina DePian, a museum educator based in Greece, provides a detailed and accessible guide to making stop motions. Accompanied by a set of animation resources, this guide makes it easy for anyone from 5 to 105 to try animation and create their own version of antiquity.

Teaching Ancient Greece is an action-packed set of resources to make learning enjoyable, challenging, and memorable. Download your free copy here:

https://www.wuw.pl/product-eng-19615-Teaching-Ancient-Greece-Lesson-Plans-Vase-Animations-and-Resources-PDF.html

Post by the OMC Team, placed by Olga Strycharczyk.

***

Our Mythical Childhood website (ERC Consolidator Grant): http://omc.obta.al.uw.edu.pl/

The Modern Argonauts website (ERC Proof of Concept Grant): https://modernargonauts.al.uw.edu.pl/