This post was written by Rachel Rajamoney as an assignment for module Art & Life in the Ancient World, led by Katerina Volioti, Lecturer in History at the University of Roehampton. We invite you to read other posts prepared by the University of Roehampton international students:

– Ancient and Modern Entanglements: Roman Wall Paintings by Rhianna Wallace,

– How Did Statues Change from the Archaic to the Classical Period? by Lauren Husz.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to Professor Katarzyna Marciniak for enabling, once again this year, the publication of student work in the blog of international research project Our Mythical Childhood. International collaborations mean a lot to the Study Abroad Team of the University of Roehampton, and to me personally, Katerina Volioti, as teacher and facilitator of multidisciplinary modules in practical Humanities.

***

My name is Rachel Rajamoney, and I’m currently pursuing a B.S. in Data Science with a minor in Mathematics at Texas Christian University, where I’m also a member of the John V. Roach Honors College. I’m studying abroad this term (Spring 2025) at the University of Roehampton in London, which has given me the opportunity to engage deeply with interdisciplinary perspectives, particularly through the Art & Life module. This class challenged me to look beyond data and code and consider the cultural and embodied dimensions of ancient artifacts.

Through this assignment, I’ve not only developed stronger research and analytical skills, but also advanced my abilities in public speaking, visual communication, and critical storytelling – skills that are essential both in academic and professional environments. My academic background in artificial intelligence and data science shaped how I approached the digital museum critique, especially in recognizing the missed potential for immersive and interactive technologies like VR, haptics, and AI-driven storytelling to restore context and meaning to historical objects.

As someone aspiring to a career that bridges quantitative analysis and strategic decision-making, whether in capital markets, technology, or cultural analytics, this experience reminded me that data is not just numerical. It is narrative. Digital humanities and AI can play a powerful role in revitalizing our relationship with the ancient world, not by replacing human interpretation, but by expanding access, interactivity, and imagination in how we engage with the past.

Before I begin, I’d like to acknowledge the remarkable efforts of curators and museum professionals who care for ancient objects like the Portland Vase. While my presentation offers a critique of certain curatorial approaches, it is not intended to diminish their work. Rather, I approach this as an engaged member of the public – someone with a strong interest in both material culture and digital innovation. I hope to contribute constructively to ongoing conversations about how museums might experiment with new tools that enhance public understanding, especially through sensory engagement and storytelling. This presentation is offered in the spirit of shared curiosity and collaborative improvement.

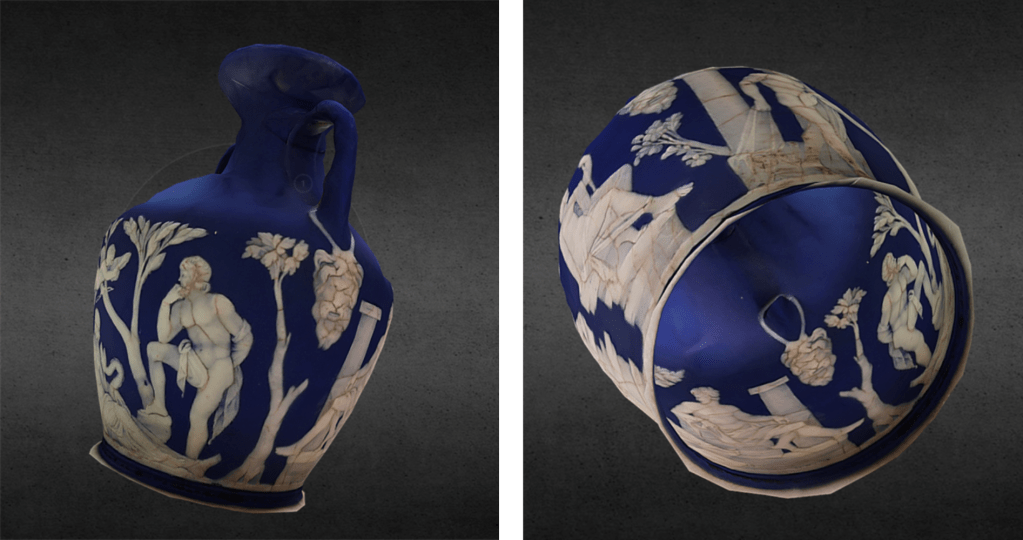

In elite Roman symposia, the Portland Vase was no passive ornament but an active participant in wine service and hospitality. While other Roman glass vessels existed, none matched the Portland Vase’s technical sophistication or narrative complexity, it remains unparalleled. William Gudenrath, Kenneth Painter, and David Whitehouse’s technical analysis reveals the vase was blown and cased with opaque white over deep blue glass, then meticulously carved, a process requiring such precision that modern reproductions often fail.[2] Maude Haywood notes, in The Decorator and Furnisher, that even Wedgwood’s famed reproductions couldn’t replicate its layered glass technique.[3] This confirms its status as a masterwork of Roman glass technology. When handled during symposia, its mythological scenes – such as that of Peleus and Thetis – provoked philosophical discourse about desire and restraint. The vase became an item of otium, with its luxurious materiality reflecting the elite’s leisure while its myths exposed their vulnerability. Servants transported it between triclinia with ritual care, its fragility underscoring its status, until ultimately accompanying its owner as a funerary object, completing what Newby calls the performance cycle of Roman identity.[4]

This vase acted on people: its beauty commanded reverence, its myths provoked intellectual discourse about morality and human nature. It was multisensory: seen, held, and debated. This was bodily entanglement: the vase mediated social bonds, much as Ian Hodder describes in Entangled: An Archaeology of the Relationships Between Humans and Things – objects act on us as we act with them.[5] Its myths weren’t mere decoration. They sparked sophisticated debates about power and desire, reflecting the owner’s paideia (education) and otium (elite leisure, opposite of negotium, referring to business and political activity). Buried with elites, it transitioned from status symbol to funerary companion, reflecting what Zahra Newby calls identity curation through Greek myths.[6] The vase was a conversation piece in the deepest sense: literally passed around, critically examined, and interpreted through learned discussion.

But this entanglement required intimacy: the warmth of hands and the sound of thoughtful voices.[7] How does that translate today?

Today, the Portland Vase is preserved behind glass in a climate-controlled case in Gallery 70. At present, the British Museum does not offer a three-dimensional (3D) model of the vase. The online platform Sketchfab, however, features a 3D model.[8] However, while helpful, these features only partially convey the object’s materiality. The 3D model allows for rotation, but it lacks cues for scale or sensory context – what American Journal of Archaeology (AJA) reviewers criticize as “decontextualized beauty”. As the AJA’s review “Online Encounters with Museum Antiquities” notes, museums remain primary sites of exchange yet often provide only partial digital access.[9] As Romina Delia writes in “Performances. Contemporary Encounters in Historic Spaces” in The Contemporary Museum: Shaping Museums for the Global Now, museums risk becoming “stages without actors” when they overlook storytelling.[10] Here, the vase remains a silent actor. The vase’s potential for theatrical digital storytelling, such as VR experiences simulating symposia or interactive touch replicas, remains largely untapped.

This is not to criticize but to imagine what might be possible. A more immersive and interpretive approach could enrich the museum’s educational mission by reviving the vase’s embodied social life. While the entry documents materials and style, it could build on that foundation with richer contextual experiences – an exciting opportunity for deeper engagement.

Compare this to the Metropolitan Museum’s Boscoreale Villa recreation, where visitors virtually enter a complete Roman dining room that mirrors the original context of vessels like the Portland Vase. Other museums, like the Digital Museum of the Acropolis Museum in Athens, also offer innovative ways to contextualize artifacts through virtual environments. For the Portland Vase, similar tools could simulate handling, letting users feel its weight or pour virtual wine while immersed in its proper architectural setting. The MET’s approach aligns with the International Council of Museums (ICOM), which calls for museums to foster dialogue, not merely display. According to ICOM, “A museum is a not-for-profit, permanent institution in the service of society that researches, collects, conserves, interprets and exhibits tangible and intangible heritage. Open to the public, accessible and inclusive, museums foster diversity and sustainability. They operate and communicate ethically, professionally and with the participation of communities, offering varied experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection and knowledge sharing”.[11]

While the British Museum emphasizes global dialogue, the Portland Vase is presented as a timeless relic. Even the lighting in displays, whether in person or online, can sterilize objects, removing shadows and tactile cues. The vase becomes art, not a lived object. As Hodder argues in Entangled: An Archaeology of the Relationships Between Humans and Things, entanglement is multisensory. To fully activate the museum’s educational potential, institutions might explore new digital strategies such as VR recreations of Roman villas or curated digital symposia. As Mary W. Hudson notes in the Fine Arts Journal, the vase’s modest 25 cm scale belies its artistic and social significance.[12] The current dissonance between ancient use and modern presentation signals a compelling opportunity for digital storytelling – not as criticism, but as collaborative imagination.

The BM’s online entry could also benefit from curator voices and layered interpretations – what Cintia Velázquez Marroni calls “expert dialogues” in the “Pasts. Authoring National Histories in the Contemporary City” in The Contemporary Museum: Shaping Museums for the Global Now.[13] Why not a digital symposium or interactive educational module as seen with other Roman objects? These suggestions aim to support, not replace, existing efforts by highlighting ways to expand the museum’s digital reach.

The vase’s itinerary, from tactile Roman rituals to pixelated isolation, reveals a choice. While common Roman glassware existed, the Portland Vase’s uniqueness demands exceptional care in its digital presentation. Institutions could look to models like the Vatican’s embodied digital strategies, such as their virtual Sistine Chapel tour, to inspire similar efforts for ancient artifacts.[14] These strategies could allow viewers to engage with the vase through sound, movement, and storytelling. While the British Museum’s online entry provides scholarly data, it strips away the object’s ancient social and sensory entanglements. For the vase to remain culturally alive, museums may need to work harder to bridge the gap between artifact and audience, transforming static displays into dynamic encounters. True preservation means reviving an object’s relationships, not just conserving its form.

In closing, I want to emphasize that my critique arises from deep admiration for the Portland Vase and the institutions that care for it, including the British Museum and others. The British Museum has preserved this masterpiece for future generations, and its online access is an important step. My hope is that this presentation contributes to a wider conversation about how we might build on such foundations, by experimenting with more immersive storytelling, multi-sensory experiences, and interactive formats. These are exciting opportunities for museums to expand their already valuable educational role.

[1] “amphora; vessel (closed); cameo [The Portland Vase]”, The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1945-0927-1 (accessed 4 March 2025).

[2] William Gudenrath, Kenneth Painter, and David Whitehouse, “The Portland Vase”, Journal of Glass Studies 32 (1990), 14, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24188029 (accessed 29 July 2025).

[3] Maude Haywood, “The Portland Vase”, The Decorator and Furnisher 14.1 (Apr. 1889), 25, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25585785 (accessed 29 July 2025).

[4] Zahra Newby, Greek Myths in Roman Art and Culture: Imagery, Values and Identity in Italy, 50 BC–AD 250, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016, 1–31.

[5] Ian Hodder, Entangled: An Archaeology of the Relationships Between Humans and Things, Oxford: Wiley–Blackwell, 2012, 89.

[6] Zahra Newby, ibidem.

[7] Jesús Muñoz Morcillo, “[Review of] The Embodied Object in Classical Antiquity by Milette Gaifman, Verity Platt, and Michael Squire”, Bryn Mawr Classical Review (2019), 2019.05.52, https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2019/2019.05.52 (accessed 4 August 2025).

[8] “Copy of the Portland Vase, 3D model”, Sketchfab, 2022.04.07, https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/copy-of-the-portland-vase-667c25404a074d6389da9a6207098d7f (accessed 29 July 2025).

[9] Caitlin Chien Clerkin and Bradley L. Taylor, “Online Encounters with Museum Antiquities”, American Journal of Archaeology 125.1 (January 2021), 173, https://ajaonline.org/museum-review/4249 (accessed 4 March 2025).

[10] Romina Delia, “Performances. Contemporary encounters in historic spaces” in Simon Knell, ed., The Contemporary Museum: Shaping Museums for the Global Now, London: Routledge, 2018, 128–129.

[11] “Museum Definition”, International Council of Museums, https://icom.museum/en/resources/standards-guidelines/museum-definition (accessed 4 March 2025).

[12] Mary W. Hudson, “The Portland Vase”, Fine Arts Journal 30.1 (1914), 48–49, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25587222 (accessed 29 July 2025).

[13] Cintia Velázquez Marroni, “Pasts. Authoring national histories in the contemporary city”, in Simon Knell, ed., The Contemporary Museum: Shaping Museums for the Global Now, London: Routledge, 2018, 152–153.

[14] “Sistine Chapel”, The Holy See, http://www.vatican.va/various/cappelle/sistina_vr/index.html (accessed 4 March 2025).

Bibliography

“amphora; vessel (closed); cameo [The Portland Vase]”, The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1945-0927-1 (accessed 4 March 2025).

“Copy of the Portland Vase, 3D model”, Sketchfab, 2022.04.07, https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/copy-of-the-portland-vase-667c25404a074d6389da9a6207098d7f (accessed 29 July 2025).

“Cubiculum (bedroom) from the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/247017 (accessed 4 March 2025).

“Museum Definition”, International Council of Museums, https://icom.museum/en/resources/standards-guidelines/museum-definition (accessed 4 March 2025).

“Sistine Chapel”, The Holy See, http://www.vatican.va/various/cappelle/sistina_vr/index.html (accessed 4 March 2025).

Clerkin, Caitlin Chien and Bradley L. Taylor, “Online Encounters with Museum Antiquities”, American Journal of Archaeology 125.1 (January 2021), 165–175, https://ajaonline.org/museum-review/4249 (accessed 4 March 2025).

Delia, Romina, “Performances. Contemporary encounters in historic spaces” in Simon Knell, ed., The Contemporary Museum: Shaping Museums for the Global Now, London: Routledge, 2018, 128–141.

Gudenrath, William, Kenneth Painter, and David Whitehouse, “The Portland Vase”, Journal of Glass Studies 32 (1990), 14–23, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24188029 (accessed 29 July 2025).

Haywood, Maude, “The Portland Vase”, The Decorator and Furnisher 14.1 (Apr. 1889), 24–25, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25585785 (accessed 29 July 2025).

Hodder, Ian, Entangled: An Archaeology of the Relationships Between Humans and Things, Oxford: Wiley–Blackwell, 2012.

Hudson, Mary W., “The Portland Vase”, Fine Arts Journal 30.1 (1914), 48–49, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25587222 (accessed 29 July 2025).

Muñoz Morcillo, Jesús, “[Review of] The Embodied Object in Classical Antiquity by Milette Gaifman, Verity Platt, and Michael Squire”, Bryn Mawr Classical Review (2019), 2019.05.52, https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2019/2019.05.52 (accessed 4 August 2025).

Newby, Zahra, Greek Myths in Roman Art and Culture: Imagery, Values and Identity in Italy, 50 BC–AD 250, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Velázquez Marroni, Cintia, “Pasts. Authoring national histories in the contemporary city”, in Simon Knell, ed., The Contemporary Museum: Shaping Museums for the Global Now, London: Routledge, 2018, 152–166.

Post by Rachel Rajamoney, tutored by Katerina Volioti, placed by Olga Strycharczyk