For Polish click here

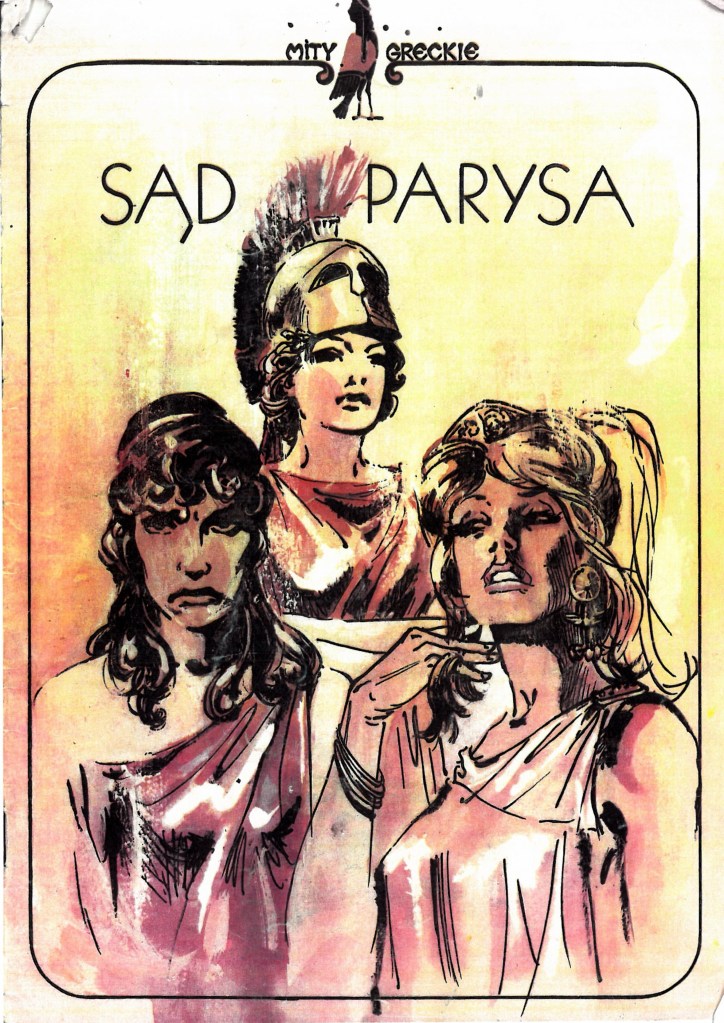

Jacek Bocheński (born 29 July 1926) – a writer and a publicist watching closely contemporary times through the prism of Antiquity; a democratic opposition activist in PRL times; winner of multiple awards. The author of The Roman Trilogy (Divine Julius 1961, Naso the Poet 1969, Tiberius Caesar 2009) translated into English (2022–2023), a collection of essays Antyk po antyku (Antiquity after the Antiquity 2010, nominated for Nike Literary Award), also the author of comic books: Sąd Parysa (Judgement of Paris 1986) and Atalanta. Najlepsza biegaczka świata (Atalanta. The World’s Best Runner 1991). The Judgement of Paris was published anonymously. Due to Bocheński’s opposition activities, he was banned from publishing many times and censored, and also interned during martial law. He used to write a blog, which appeared in print (Blog 2016, Justyna 2018, Ujście 2021).

Here, we would like to cordially thank Mr Jacek Bocheński for his time spent on the interview and for the open-heartedness he always shows to researchers of Antiquity, also to those at the very beginning of their path.

Aleksandra Płońska – a graduate of artes liberales curriculum at the Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, University of Warsaw. Inspired by the classes Comic Book – Internal Pages. Individual Artistic Training by Dr Przemysław Kaniecki and the seminar Our Mythical Childhood led by Prof. Katarzyna Marciniak, when these comic books were discussed, and also by the Graeco-Roman mythology and Jacek Bocheński’s works, she interviewed Jacek Bocheński and, under the guidance of Dr Hanna Paulouskaya, wrote a master’s thesis Reception of Mythology in Jacek Bocheński’s Comic Books. An Analysis of “Judgement of Paris” and “Atalanta” (2023). Here, we present fragments of her thesis.

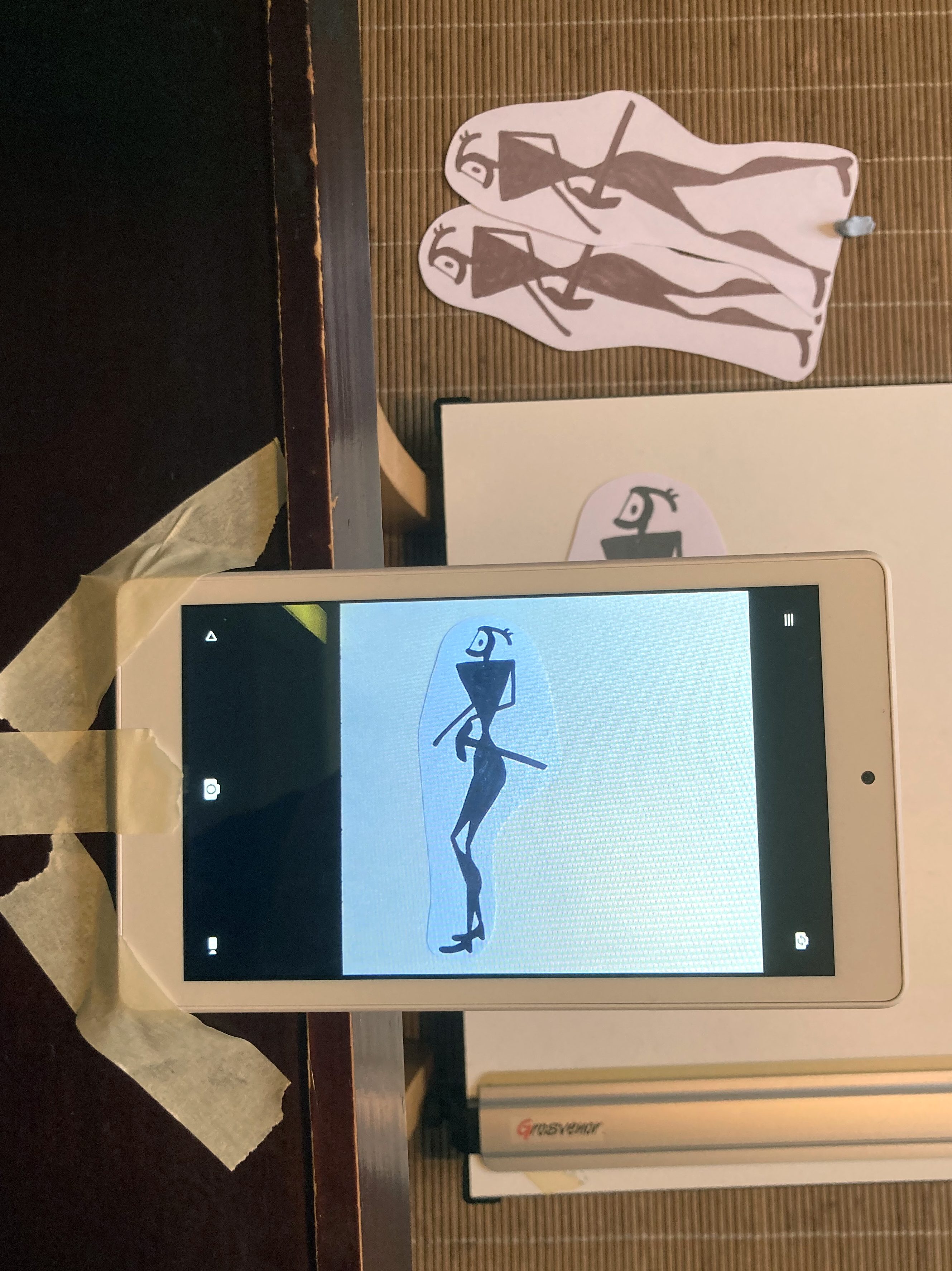

The primary sources for my MA thesis were two comics by Jacek Bocheński – Judgement of Paris, printed in 1986, and Atalanta. The World’s Best Runner, created five years later. Both works were published by the Polish publishing house – Wydawnictwo Sport i Turystyka, founded in 1953 in Warsaw, specializing in tourist catalogues, guides, sports publications, as well as comic books until 1990, when it was transformed into a separate editorial office of another publisher – Oficyna Wydawnicza Muza. The Judgement of Paris of 1986 was graphically designed by Marek Szyszko, Polish book illustrator and till 1990 also comic books illustrator. Zdzisław Byczek was commissioned to produce the graphic design of Atalanta.

Jacek Bocheński engaged in depicting two myths well known in culture, retold and developed many times by different authors interested in Greek and Roman mythology, because of the offer given to him by the editors. The Author, not considering himself a mythology specialist, wanted to create stories with bits of humour, in a witty form, if possible. He made use of sources available in the 1980s, among them Mythology by Jan Parandowski and Greek Myths by Robert Graves.

The Judgement of Paris is an adaptation of an ancient myth, supplied with contemporary meanings and methods of presenting stories. This comic book, because of its humorous, informal language, is directed to teens and young adults, but its design changes the perspective and appeals to older readers as well. In particular, the myth, stripped of cruel elements of the story yet retaining mature visual aspects, was adapted for readers over the age of thirteen. It not only deepens their knowledge of mythology, but also educates on aspects of democracy, stresses the role of sport culture in the life of a young man, and draws attention to the problem society struggles with – devaluation of values and instead focus on physical attractiveness. The comic book tells the whole story of the Judgement of Paris in detail, so that readers can dive into reading without any specific knowledge of mythology, and at the same time, it broadens some aspects of the myth, drawing readers into more extensive ancient threads.

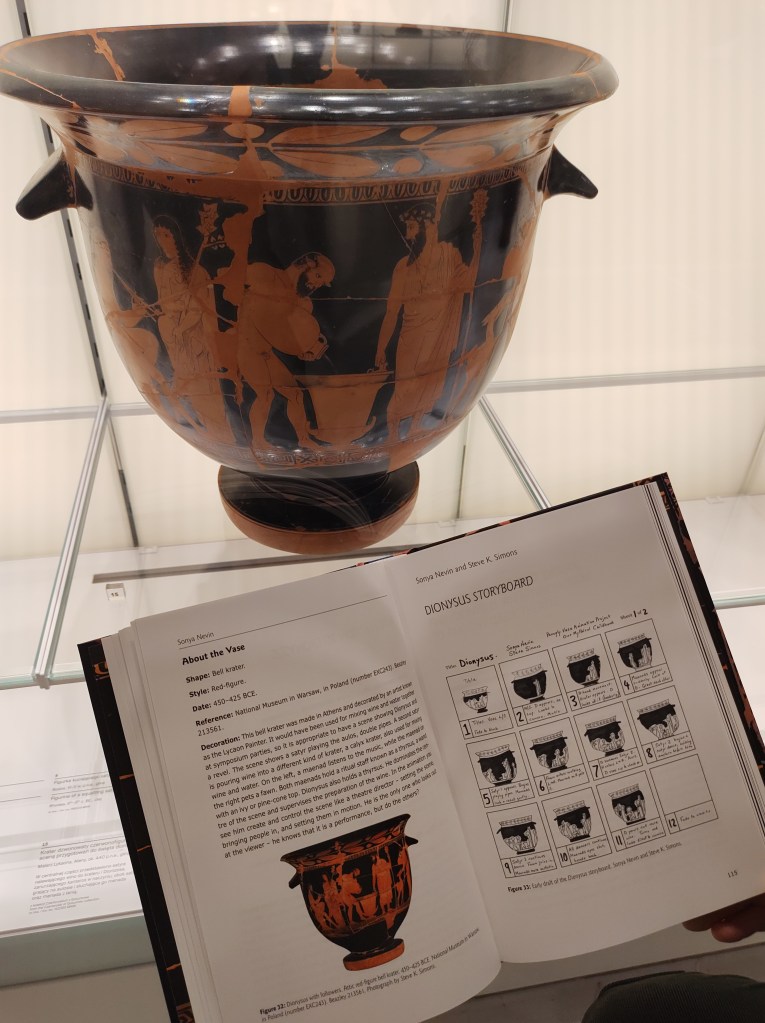

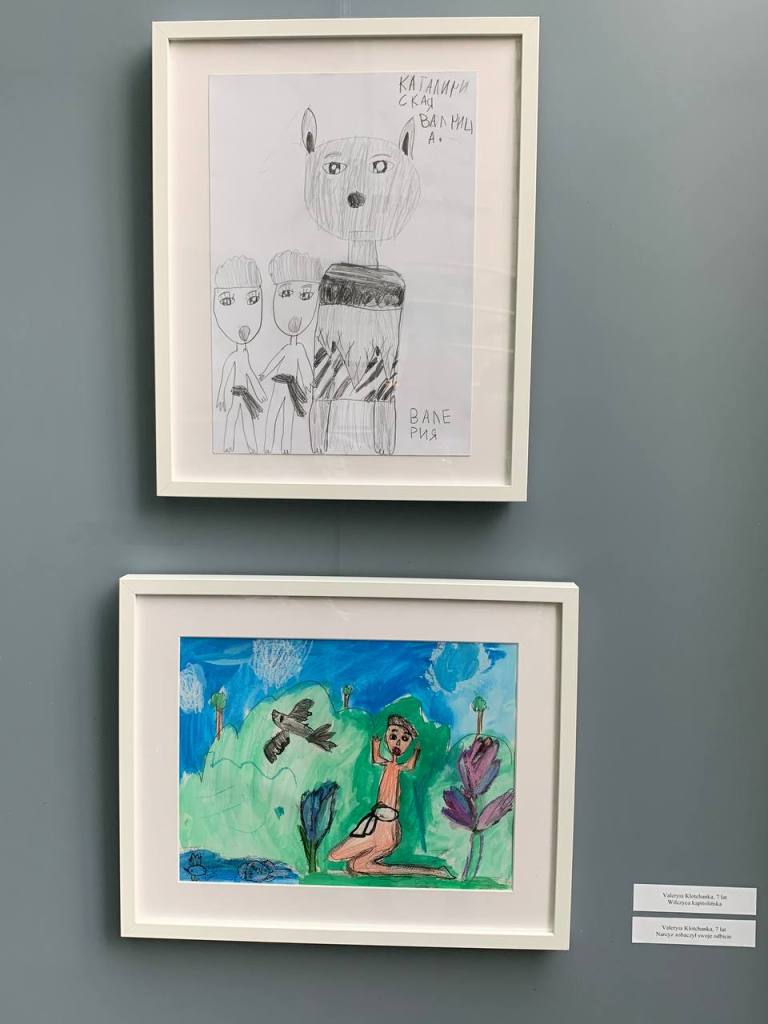

The Judgement of Paris met the taste of the editors of Sport i Turystyka, so they asked Bocheński if he would like to write another story. This time, the author chose the myth about the runner to refer to the subject of the magazine. The myth about Atalanta, repeated in culture since ancient times, has several inconsistent versions; however, it is most commonly associated with the Calydonian Hunt. The writer pointed out the double message of this ancient story and included in his work an alternative ending characteristic of ancient myths, which were often told in several versions. Therefore, he attempted to give the reader an unobvious mythological element to awaken curiosity for further research on their own. A broad narration of a comic gave a chance to fully tell the story of the heroine who can be interpreted through a feminist prism and influence young readers’ view on the situation of women in the world. The style of illustrations modelled on ancient characters known from famous sculptures and ancient depictions educates readers, showing them the past and inspiring them, at the same time, to appreciate the beauty of art history. The book is filled with many ancient motifs, such as clothes and characteristic ornaments, bringing young adults closer to Graeco-Roman culture. A contemporary thread that stands out is the ecological sensitivity of the main character of Artemis, but also, in contrast, the cruelty of humans towards animals.

Jacek Bocheński, in his series The Roman Trilogy, was trying to mirror the situation of contemporary people and, through allegorical language, draw attention to the reality in Poland and the world. The analysis of his comic books leads to the conclusion that the Author does not attempt to influence readers in his country but rather to use it as a didactic tool for imparting knowledge. At the same time, the comics reinterpret ancient myths in relation to contemporary problems and values, while also teaching lessons relevant to everyday life. Visual measures enabled him to create interesting material that disseminates cultural heritage through innovative depictions, allowing Jacek Bocheński to create engaging content that conveys cultural heritage through innovative depictions of mythology. All components: the cover, the title, the narrative introduction, and also the additional text complementary to the story are crucial points during the read – introduce the readers to the world of myths, broaden their knowledge on mythology, and lead them through the depicted story.

The comic books are an unusual chapter among the Author’s oeuvre. He usually addressed his works to adult readers, familiar with ancient culture. A perfect command of the historical and literary background allowed Bocheński to choose a range of topics suitable and clear to a young reader to sneak in valuable moral tips and to invite youth to further research on Antiquity. Bocheński was very agile in adapting the original content of the myths to a genre unusual for him. Despite the necessary simplifications the content remained rich in universal values and unobvious pretexts to reflect on Antiquity.

I don’t know much about comic books, but it fell to me to create one.

– Jacek Bocheński in an interview by Aleksandra Płońska, 2023

Aleksandra Płońska: Did you read comic books, e.g., typical comics from the USA, about superheroes (if they were available in Poland)? Do you like this literary form?

Jacek Bocheński: Well, no. I know very little about the comic book culture. These were never my kind of books, and I was not interested in comics. In general, I knew only what its structure was and what needed to be done. The pictures should show figures or stories and very little text in speech balloons coming out of the mouth, and that is what I knew about comic books. And that there is some generally recognised graphic convention to draw those pictures, and the characters have a specific appearance.

Why comics then? Was it your idea?

The offer came from the weekly magazine – Sport i Turystyka, a publisher fairly distant from my interests. After all, I have never written about sport. They asked me if I could produce something popular about ancient myths in a comic book form. I thought to myself – fine, I cannot refuse such an outstretched hand. I won’t say “it is not a job for me, I don’t do that kind of things”, and said: okay, I’ll think about it. I decided this could be an interesting task. How to write it, what to do with it? I made up something I could not finally get through with: a visual artist should look at iconography of Greek vases and see how the mythical characters were depicted and, using own invention, own artistic creation, try to transfer them to a comic book, that is not to draw routinely, like it used to be in popular American comics, rather to show some entirely new, distinct style. This was my idea for the artistic part, this is how I primarily imagined it. I used to do something similar with novels: I was trying to create a very easy and interesting story based on ancient written sources and adapt it to a new literary form. However, it turned out that my idea was impossible to carry out.

Why did you choose these myths in particular and not others?

The myth about the Judgement of Paris seemed to me convenient to design graphically: fairly simple, intriguing, with goddesses competing to see which of them is the most beautiful. Comics is a kind of drawn, tiny theatre play, isn’t it? I don’t know much about comic books, but it happened that I had to create one. So I needed to stage such a show where I could put very little text but also describe what is going to be in the picture, give information to the illustrator. I wrote this story in a humorous form, which Sport i Turystyka liked very much – they published it and wanted another one. And I knew it was a publisher of a certain profile, so the Greek myths I compiled should have something in common with sports and tourism. Tourism in a contemporary meaning was not a thing in Antiquity, so this seemed problematic. Whereas I drew their attention to the motif of competitiveness, which was very important in ancient (Greek) culture and present in many domains: artists competed with each other, and there were held games which are a prototype of our sport. Ancient Greeks thought about what we call sport as something that makes a man stand out. They did not do it for profit; it was pure amateur – they did it for their own ambition, to prove themselves as capable people, capable of jumping far, running fast, driving the chariot.

Hence, for example, Atalanta? It is not a well-known myth…

But the runner! I found a runner – it’s just perfect for the publisher!

What is the reason for the difference in form of comics about Paris and Atalanta? The first one was printed in 1986 and the second in 1991 – this is five years difference.

The second one isn’t a comic. It is a narrative, a brief story. Why? Because Janusz Stanny, who drew illustrations, was visiting Switzerland and showed them to someone, and they were bought by a Swiss publisher. Stanny, without consulting the publisher, simply sold them, disregarding the previous contract with Sport i Turystyka, as well as the one with me. I faced a situation where this comic book was not to be published. The editors of Sport i Turystyka commissioned new illustrations from Byczek, except it wasn’t going to be a comic book anymore. They asked me to write a short story based on the narrative from the script.

And yet, it seems the Atalanta is more reminiscent of a comic book than the Judgement of Paris. The Judgement has, in fact, more dialogue bubbles, Atalanta has many narrative descriptions. Descriptions are not rare in comics, but Atalanta is divided into so-called panels. Judgement of Paris has full-page drawings, without any division.

Interesting. I suppose you will address this in your thesis?

Yes, I will try to describe the technical differences between the two comics. I’m also interested in what the assumption was, regarding the readers, what was the aim? Was it simply to introduce them to these myths?

This was my aim, an educational and didactic aim. For the rest, I think Prof. Marciniak understands it very well. She is the author of My First Mythology, a book for children. It is a charming book. It combines its lightness, flow in the simplest story, always with some portion of educational information that enriches children’s knowledge while being also a book for adults. You can also read My First Mythology at my age and laugh out loud. A lovely book. That’s how Ms Marciniak writes.

A notable feature of Atalanta is that it has a second ending. I suppose that you didn’t stick to a single ending is a typical mythological measure.

Oh, yes, there are two versions; we have a double message. I had an ambition to also pass this information to my readers. If the myth functioned in Antiquity in two different versions, my readers should be aware of it. And I won’t lecture them like a professor; it is just not my way of approaching readers, so I will explain it to them in a different, easier way.

So access to myths across different generations?

Yes, and passing on myths in various forms, accessible to various generations.

Whose mythologies do you consider the best, and, regarding these comics, what contemporary or ancient sources did you use?

When thinking about the authors of mythologies, one Polish author comes to mind, and his name is Zygmunt Kubiak. And imagine that when I created the Judgement of Paris as a comic book scenario, I thought I should show it to someone who knows the subject, because I didn’t consider myself a mythology expert. I read, of course, Parandowski and Graves, and used many other sources of information, even encyclopaedias, various available sources. But because I knew Zygmunt Kubiak, I called him and asked if he would like to meet with me. So we agreed to meet at a café, but he didn’t know why. I took the script of the Judgement of Paris with me, we ordered coffee and I gave Mr Zygmunt my pages (it was not a long read). I asked him to tell me if I made any mistakes. He read it and made a very serious face – so I immediately thought “oh no… I wrote some rubbish there”. And he said: why did you write this? This is not for you! You should stick to doing the serious stuff you are good at, not such nonsense. And the conversation ended. Since then, I was hiding from Zygmunt Kubiak, thinking I had absolutely discredited myself. But, you know, Zygmunt Kubiak had a completely different view on mythology. For him, it wasn’t something to be retold in a modern context and an opportunity for jokes, but a deep reflection on ancient culture. And it was a man approaching his profession very solemnly, unbelievably serious, so he believed it was a silly joke, and he wouldn’t be dealing with something like that. Plus, he remarked that I could do something wiser.

Why did you publish the Judgement of Paris anonymously?

Firstly, it was necessary to hide this from the authorities. I was the editor of the first literary magazine of the Polish underground press, Zapis, which we created in 1976. It was published for five years, and then the martial law was imposed, during which I was interned, because, as you know, at that time people from the opposition were subjected to certain persecutions, not as severe as in other times of that regime, but that was under the rule of general Jaruzelski and his military. Anyway, the authorities were not supposed to know that I published in Sport i Turystyka, as it could cause some trouble for the editorial office.

The second reason was that comic books were not appreciated by everyone, Zygmunt Kubiak is the best example. So I chose to use a pseudonym also out of embarrassment.

So why didn’t you decide to continue then?

I don’t think they approached me with any further projects. But I admit I may not remember very well, it was thirty years ago.

More about Jacek Bocheński works:

The website of Jacek Bocheński

https://jacekbochenski.home.blog

Jacek Bocheński about Divine Julius

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f0_G_KW2uJw

Fragments of the translation of The Roman Trilogy

https://www.mondrala.com/divinejulius

45 Seconds Reception: Divine Julius by Jacek Bocheński

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f0_G_KW2uJw

Prof. Katarzyna Marciniak about The Roman Trilogy

https://antigonejournal.com/2023/06/jacek-bochenski-roman-trilogy

Jacek Bocheński on Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacek_Boche%C5%84ski

Post by Aleksandra Płońska, placed by Olga Strycharczyk; the English version by Olga Strycharczyk, proofread by Elżbieta Olechowska

Sąd Parysa i Atalanta w komiksach Jacka Bocheńskiego

Jacek Bocheński (ur. 29 lipca 1926 r.) – pisarz i publicysta przyglądający się współczesności przez pryzmat antyku, działacz opozycji demokratycznej w PRL, wielokrotnie nagradzany. Autor m.in. Trylogii rzymskiej (Boski Juliusz 1961, Nazo poeta 1969, Tyberiusz Cezar 2009) przetłumaczonej na język angielski (2022–2023), zbioru esejów Antyk po antyku (2010, nominowanego do Nagrody Literackiej Nike), także autor komiksów: Sąd Parysa (1986) i Atalanta. Najlepsza biegaczka świata (1991). Sąd Parysa opublikował anonimowo, ponieważ ze względu na działalność opozycyjną Bocheński często mierzył się z zakazem druku i cenzurą, a w trakcie stanu wojennego był internowany. Prowadził blog, który został opublikowany także drukiem (Blog 2016, Justyna 2018, Ujście 2021).

W tym miejscu pragniemy bardzo serdecznie podziękować Panu Jackowi Bocheńskiemu za czas poświęcony na wywiad i za serdeczność, którą zawsze okazuje badaczom antyku – także tym na samym początku drogi naukowej.

Aleksandra Płońska – absolwentka kierunku artes liberales na Wydziale „Artes Liberales” Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego. Z inspiracji zajęciami Dr. Przemysława Kanieckiego Komiks – strony wewnętrzne. Indywidualne Szkolenie Artystyczne oraz seminarium Nasze Mityczne Dzieciństwo prowadzonym przez Prof. Katarzynę Marciniak, w trakcie którego omawiane były te utwory, a także mitologią grecko-rzymską i twórczością Jacka Bocheńskiego, przeprowadziła wywiad z Jackiem Bocheńskim i przygotowała pod kierunkiem Dr Hanny Paulouskaya pracę magisterską Recepcja mitologii w komiksach Jacka Bocheńskiego. Analiza “Sądu Parysa” i “Atalanty” (2023). Fragmenty pracy prezentujemy w niniejszym poście.

Materiałem mojej pracy magisterskiej były dwa komiksy autorstwa Jacka Bocheńskiego – wydany w 1986 roku Sąd Parysa oraz powstała pięć lat później Atalanta. Najlepsza biegaczka świata. Oba utwory opublikowało polskie Wydawnictwo Sport i Turystyka, które zostało założone w 1953 roku w Warszawie i specjalizowało się zarówno w informatorach turystycznych, przewodnikach, opracowaniach sportowych, jak i publikacjach komiksów aż do lat 90., kiedy to zostało przekształcone w odrębną redakcję Oficyny Wydawniczej Muza. Opracowaniem graficznym Sądu Parysa z 1986 roku zajął się Marek Szyszko, polski ilustrator książek i do 1990 roku rysownik komiksów. O realizację ilustracji komiksowych Atalanty redaktorzy poprosili Zdzisława Byczka.

Jacek Bocheński podjął się przedstawienia dwóch znanych w kulturze mitów, wielokrotnie opracowywanych i przerabianych przez kolejnych twórców, interesujących się mitologią Greków i Rzymian, ze względu na propozycje ze strony redaktorów z wydawnictwa. Autor, nie uważając się za znawcę mitologii, chciał stworzyć historie z elementami komizmu, w formie w miarę możliwości dowcipnej. Korzystał zatem z dostępnych w latach 80. źródeł, w tym z Mitologii Jana Parandowskiego i Mitów greckich Roberta Gravesa.

Sąd Parysa stanowi adaptację antycznego mitu, zaopatrzoną we współczesne znaczenia i metody prezentowania opowieści. Komiks, poprzez żartobliwy, swobodny język, treściowo przeznaczony jest dla młodzieży, warstwa graficzna zmienia jednak perspektywę i sytuuje go w grupie starszych odbiorców. W szczególności mit, okrojony z okrutnych elementów przekazu, zawierający jednak dojrzałe aspekty wizualne, został dostosowany do odbiorców powyżej trzynastego roku życia. Nie tylko pogłębia ich wiedzę z zakresu mitologii, lecz także edukuje w kwestiach demokracji, podkreśla rolę kultury sportowej w życiu młodego człowieka oraz zwraca uwagę na problem, z jakim zmaga się społeczeństwo – dewaluację wartości na poczet atrakcyjności fizycznej. Komiks szczegółowo i w całości opowiada historię Sądu Parysa, dzięki czemu czytelnik może przystąpić do lektury bez konkretnej wiedzy mitologicznej, a jednocześnie rozszerza pewne aspekty mitu, wciągając odbiorcę w obszerniejsze wątki starożytności.

Sąd Parysa przypadł redaktorom Sportu i Turystyki do gustu, zwrócili się więc do Bocheńskiego z prośbą o napisanie kolejnej historii. Tym razem pisarz, żeby zbliżyć się do tematyki samego wydawnictwa, odnalazł mit o biegaczce. Mit o Atalancie, powielany w kulturze od starożytności, doczekał się kilku niespójnych wersji – historia dziewczyny najbardziej jednak kojarzona jest z wątkiem łowów kalidońskich. Pisarz zwrócił uwagę na dwoistość przekazu antycznej historii i zawarł w swoim dziele alternatywne zakończenie, charakterystyczne dla starożytnych mitów, które często funkcjonowały w kilku wersjach. Podjął zatem próbę przekazania czytelnikowi nieoczywistego elementu mitologicznego, chcąc rozbudzić ciekawość do dalszych, samodzielnych poszukiwań. Przestronna narracja komiksu pozwoliła na pełne opowiedzenie historii bohaterki, której postać można odczytać przez pryzmat feministyczny, mogący zmienić światopogląd młodego odbiorcy na sytuację kobiet w otaczającym świecie. Styl ilustracji, wzorowanych na antycznych postaciach znanych z rzeźb i obrazów starożytnych, edukuje czytelników, ukazując im nieobecny współcześnie świat i zachęcając jednocześnie do wkroczenia w piękno historii sztuki. Komiks został opatrzony wieloma motywami starożytnymi, takimi jak stroje czy charakterystyczne ornamenty, przybliżającymi młodzież do kultury grecko-rzymskiej. Współczesnym wątkiem wybijającym się na tle innych jest wrażliwość ekologiczna zarówno głównej bohaterki, jak i Artemidy, a także usytuowane w przeciwieństwie do nich okrucieństwo ludzi wobec zwierząt.

Jacek Bocheński w swojej serii książek Trylogia rzymska próbował odzwierciedlić sytuację ludzi współczesnych oraz poprzez alegoryczny język zwrócić uwagę na realia panujące w Polsce i na świecie. Analiza jego dzieł komiksowych pozwoliła ustalić, że Autor poprzez tematy mitologiczne nie usiłuje wpływać na opinię publiczną w kraju, lecz traktuje je jako narzędzie edukacyjne do przekazywania wiedzy. Jednocześnie jego komiksy reinterpretują antyczne mity w odniesieniu do aktualnych problemów i wartości oraz przekazują naukę, mającą znaczenie w życiu codziennym. Wizualne możliwości stworzyły ciekawy materiał, przyczyniający się do przekazywania czytelnikom dziedzictwa kulturowego poprzez nowatorski sposób przedstawiania mitologii. Wszystkie składniki okalające, takie jak okładka, tytuł, narracyjny wstęp czy dodatkowy tekst dopełniający dany utwór wprowadzają odbiorcę w świat mitów, poszerzają jego wiedzę mitologiczną oraz prowadzą go przez opisywaną historię, będąc niezbędnymi punktami podczas lektury.

Komiksy stanowią nietypowy rozdział w dorobku literackim Autora, który zazwyczaj kierował swoje utwory do czytelnika dojrzałego, obytego z kulturą antyczną. Doskonała znajomość tła historycznego i literackiego mitów pozwoliła Bocheńskiemu wybrać odpowiedni i czytelny dla młodego odbiorcy zakres tematów, aby przemycić w nim wartościowe wskazówki moralne i zaprosić młodzież do dalszych badań nad antykiem. Bocheński bardzo sprawnie zaadaptował oryginalne treści mitów do gatunku nietypowego dla jego twórczości. Mimo niezbędnych uproszczeń treść pozostała nasycona uniwersalnymi wartościami oraz nieoczywistymi pretekstami do refleksji nad starożytnością.

Nie znam się na komiksach, a wypadło mi komiks stworzyć.

– Jacek Bocheński w rozmowie z Aleksandrą Płońską, rok 2023

Aleksandra Płońska: Czytał Pan komiksy, np. typowe komiksy z USA o superbohaterach (o ile były one dostępne w Polsce)? Lubi Pan taką formę literacką?

Jacek Bocheński: Otóż właśnie nie. Ja jestem bardzo słabo obyty z kulturą komiksową. To nie były nigdy moje lektury i nie interesowałem się komiksami – z grubsza tylko wiedziałem, na czym polega taka struktura komiksu i co trzeba zrobić. Powinno się ukazać rysunki (ramki), tak by w tych rysunkach mogły wystąpić figury czy jakieś opowieści i jedynie bardzo krótkie zdania w dymkach, które wylatują z ust, i to właściwie było wszystko, co wiedziałem o komiksie. Wiedziałem też, że istnieje tam pewna powszechnie uznana konwencja graficzna, że w pewien określony sposób rysuje się te obrazki, a postacie przybierają charakterystyczny wygląd.

Dlaczego zatem komiks? Czy to był Pański pomysł?

Propozycja wyszła ze strony tygodnika – Sportu i Turystyki, wydawnictwa dość dalekiego od moich zainteresowań, ja przecież nie pisałem nigdy o sporcie. Zapytali, czy mógłbym dla nich opracować coś popularnego w postaci komiksu o mitach starożytnych. Pomyślałem sobie – dobrze, nie mogę nie przyjąć takiej wyciągniętej do mnie ręki. Nie będę mówił, że to „nie jest dla mnie robota, ja się takimi rzeczami nie zajmuję”, tylko powiedziałem: dobrze, to pomyślę nad tym. Stwierdziłem, że to może być ciekawe zadanie do wykonania. Jak to napisać, co z tym zrobić? Wymyśliłem coś, czego nie udało się ostatecznie zrealizować: artysta-plastyk powinien spojrzeć na taką ikonografię z waz greckich i zobaczyć, jak te postacie mitologiczne były przedstawiane, i dzięki własnej inwencji, własnemu pomysłowi artystycznemu spróbować przenieść je do komiksu. Czyli nie robić tego komiksu rutynowo, tak jak robiło się popularne amerykańskie komiksy, tylko pokazać jakiś zupełnie nowy, inny, odrębny styl. Taki był mój pomysł od strony artystycznej, tak sobie to pierwotnie wyobrażałem. Robiłem coś takiego w powieściach: ze starożytnych źródeł pisanych próbowałem zrobić opowieść bardzo przystępną, ciekawą i dostosowaną do nowego typu dzieła literackiego. Okazało się jednak, że mojego zamiaru nie da się spełnić.

Dlaczego wybrał Pan akurat te, a nie inne mity?

Mit o sądzie Parysa wydał mi się poręczny do opracowania komiksowego: dość prosty, intrygujący, z boginiami współzawodniczącymi o to, która z nich jest najpiękniejsza. Komiks jest rodzajem narysowanej drobnej sztuki teatralnej, prawda? Nie znam się na komiksach, a wypadło mi komiks stworzyć. A więc trzeba było zrobić takie przedstawienie, gdzie mogę dać bardzo mało tekstu, ale mogę też opisać, co ma być na obrazku, podać informacje dla ilustratora. Tę historię napisałem w możliwie dowcipnej formie, co się Sportowi i Turystyce spodobało – wydali ją i chcieli następną. A ja zdawałem sobie sprawę, że oni są wydawnictwem o określonym profilu, a zatem te mity greckie, które ja opracowuję, powinny mieć coś wspólnego ze sportem, no i z turystyką. „Turystyka” w dzisiejszym znaczeniu w starożytności nie istniała, więc to sprawiało problem. Natomiast zwróciłem im uwagę na to, że w kulturze starożytnej (u Greków) motyw współzawodnictwa był bardzo istotny, obecny w różnych dziedzinach: artyści współzawodniczyli między sobą, urządzano igrzyska, które są pierwowzorem naszego sportu. Starożytni Grecy myśleli o tym, co my dziś nazywamy „sportem”, jako o czymś, w czym człowiek może się odznaczyć. Nie uprawiali go dla zysku, było to amatorstwo w czystej formie – uprawiali go dla własnej ambicji, żeby okazać się ludźmi, którzy coś potrafią – potrafią daleko skoczyć, szybko pobiec, poprowadzić kwadrygę.

Stąd na przykład Atalanta? Nie jest to znany mit…

Ale biegaczka! Wynalazłem biegaczkę, no to jest jak znalazł dla takiego wydawnictwa!

Z czego wynika różnica formy komiksu o Parysie i o Atalancie? Pierwszy został wydany w 1986 roku, a drugi w 1991 roku – to jest pięć lat różnicy.

Ten drugi nie jest komiksem. Jest narracją, takim krótkim opowiadankiem. Dlaczego? Dlatego że Janusz Stanny, który zrobił do niego ilustracje, kiedy pojechał do Szwajcarii, pokazał je komuś i szwajcarski wydawca je kupił. Stanny bez porozumienia z wydawcą je po prostu sprzedał, a umowę, którą przedtem zawarł ze Sportem i Turystyką, no i niby ze mną – zlekceważył. Zostałem postawiony w takiej sytuacji, że nie będzie tego komiksu. Wtedy redaktorzy Sportu i Turystyki zamówili u Byczka nowe ilustracje, tylko że to już nie był komiks, poprosili mnie, żeby na podstawie narracji ze scenariusza napisać raczej krótkie opowiadanie.

A jednak to chyba właśnie Atalanta bardziej przypomina komiks niż Sąd Parysa. Sąd ma faktycznie więcej dymków, Atalanta ma dużo narracyjnych opisów. Ale opisy nie są rzadkie w komiksie, natomiast Atalanta ma podział na tzw. plansze. Sąd Parysa, ma rysunki na całych stronach, bez podziału.

Ciekawe. Rozumiem, że Pani na to zwróci uwagę w swojej pracy?

Tak, spróbuję technicznie opisać, czym różnią się komiksy. Ciekawi mnie również, jakie było założenie w stosunku do czytelników, jaki był cel? Żeby po prostu poznali te mity?

Mnie taki cel przyświecał, cel oświatowo-dydaktyczny. Myślę zresztą, że bardzo dobrze rozumie to Pani Prof. Marciniak. Ona jest autorką mitologii, zresztą Mojej pierwszej mitologii dla dzieci. To jest urocza książka. Ona łączy tę swoją lekkość, płynność w najprostszej opowieści, z pewną zawsze porcją informacji edukacyjnych, takich, które wzbogacają wiedzę dziecka, a jednocześnie jest to książka również dla dorosłych. Moją pierwszą mitologię można czytać również w moim wieku i zaśmiewać się do rozpuku. Prześliczna książka. Pani Marciniak tak właśnie pisze swoje rzeczy.

Bardzo ciekawym zabiegiem w Atalancie jest zawarte tu drugie zakończenie. Myślę, że to, że Pan nie obrał jednego zakończenia, to typowo mitologiczny zabieg.

A tak, bo tam były dwie wersje, mamy przekaz dwoisty. Miałem ambicję, żeby też taką informację przekazać tym moim czytelnikom. Jeżeli mit funkcjonował w starożytności w dwóch różnych wersjach, to mój czytelnik powinien się o tym dowiedzieć. A nie będę mu tego wykładał po profesorsku, bo to nie jest mój sposób zwracania się do czytelników, więc wytłumaczę im to inną, łatwiejszą, przystępniejszą drogą.

Czyli taki dostęp mitów do różnych pokoleń?

Tak, i podawanie mitów w rozmaitych, przystępnych dla różnych pokoleń formach.

Czyje mitologie uważa Pan za najlepsze i jeśli chodzi o te komiksy to z jakich źródeł współczesnych czy starożytnych Pan wtedy korzystał?

Jak myślimy o autorach mitologii, to przychodzi nam na myśl jeden z polskich autorów, a nazywał się on Zygmunt Kubiak. I proszę sobie wyobrazić, że jak ja stworzyłem już Sąd Parysa, jako scenariusz komiksu, to pomyślałem sobie, że trzeba by to przedstawić komuś, kto się na tym zna – bo ja się nie uważałem za znawcę mitologii. Korzystałem oczywiście z Parandowskiego i z Gravesa, i z różnych innych jeszcze informacji, nawet z encyklopedii, z różnych źródeł, z których mogłem czerpać. A ponieważ znałem Zygmunta Kubiaka, to zadzwoniłem do niego i powiedziałem, że mam do niego prośbę: czy on nie zechciałby się ze mną spotkać? Umówiliśmy się zatem do kawiarni, tyle, że on nie wiedział po co. Zabrałem ze sobą napisany Sąd Parysa, zamówiliśmy sobie kawę i Pan Zygmunt dostał ode mnie te kartki (to nie była długa lektura). Poprosiłem, żeby po przeczytaniu mi powiedział, czy ja tam nie zrobiłem jakichś błędów. On to przeczytał i bardzo poważną minę zrobił – więc od razu sobie pomyślałem, „oj niedobrze… Jakieś bzdury tam napisałem”. A on mówi: po co Pan to napisał? To nie jest dla Pana! Pan powinien się zajmować poważnymi rzeczami, Pan to dobrze robi, a nie takimi głupstwami. I na tym się skończyła rozmowa. I potem już się kryłem przed Zygmuntem Kubiakiem, bo uważałem, że jestem już absolutnie skompromitowany. Ale wie Pani, Zygmunt Kubiak zupełnie inaczej patrzył na mitologię, nie jak na coś do przerobienia na coś współczesnego i nie jak na okazję do żarcików, tylko jako głęboką refleksję o tamtej kulturze. A to był człowiek bardzo solennie podchodzący do swojej profesji, niesłychanie poważny, więc uważał, że to jakiś wygłup i on nie będzie się czymś takim zajmował. Dodatkowo mnie zwrócił uwagę, że mógłbym się czymś mądrzejszym zająć.

A dlaczego wydał Pan anonimowo Sąd Parysa?

Po pierwsze, należało to ukryć przed władzami. Byłem redaktorem pierwszego literackiego pisma niezależnego obiegu wydawniczego, Zapisu, które stworzyliśmy w 1976 roku. Wychodziło przez pięć lat, a potem nastał stan wojenny, w którym mnie internowano, bo wie Pani, że wtedy ludzie z opozycji podlegali pewnym prześladowaniom – nie tak ciężkim, jak w innych czasach tamtego reżimu, ale to już były rządy generała Jaruzelskiego i jego wojskowych. W każdym razie władze nie powinny były wiedzieć, że drukuję w Sporcie i Turystyce, mogliby wtedy stwarzać redakcji jakieś trudności.

Drugi powód był taki, że komiks nie cieszył się u wszystkich uznaniem, a najlepszym przykładem, jak bardzo się nie cieszył, jest Zygmunt Kubiak. Zatem pseudonim obrałem również ze wstydu.

Czemu zatem nie zdecydował się Pan na kontynuację?

Oni już chyba nie zwracali się do mnie z żadnym następnym projektem. Ale przyznam, że już dobrze nie pamiętam, to było trzydzieści lat temu.

Więcej o twórczości Jacka Bocheńskiego:

Strona internetowa Jacka Bocheńskiego

https://jacekbochenski.home.blog

Jacek Bocheński o „Boskim Juliuszu”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f0_G_KW2uJw

Fragmenty tłumaczenia Trylogii rzymskiej

https://www.mondrala.com/divinejulius

45 Seconds Reception: „Divine Julius” by Jacek Bocheński

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f0_G_KW2uJw

Prof. Katarzyna Marciniak o Trylogii rzymskiej

https://antigonejournal.com/2023/06/jacek-bochenski-roman-trilogy

Jacek Bocheński na Wikipedii: https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacek_Boche%C5%84ski

Post Aleksandry Płońskiej, zamieszczony przez Olgę Strycharczyk.