Krzysztof Korwin-Piotrowski – television and theatre director, PhD-student and lecturer at the Faculty of ‘”Artes Liberales” of the University of Warsaw. Since 2018 he has been the chairman of the jury in the “Antyk – Kamera – Akcja!” high school competition organised within the Our Mythical Childhood project.

For Polish click here

A few months ago I travelled to Białystok, a city located in the northeast of Poland, nearing the border of Belarus and Lithuania, for the first time in my life. I was invited to see two performances: Wokół Szekspira [Around Shakespeare] starring one of Poland’s most famous actors, Andrzej Seweryn, at the Nie Teatr [No Theatre] and West Side Story, a musical by Leonard Bernstein at the Podlasie Opera and Philharmonic. Although both performances were very interesting, they are not the focus of this text. When I am in a city for the first time, I like to wander around a bit to discover it in my own way, without a precise route. However, my mother, Barbara Penderecka-Piotrowska, reminded me that her oldest brother lived in Białystok for several years, studying at the Medical Academy (now the Medical University). So I decided to find this place, i.e. Branicki Palace.

Walking from Kościuszko Square towards the Palace, I unexpectedly saw a statue of a boy holding a book or briefcase in his left hand. The sculpture was made of brass. It turned out to be a statue of the young Ludwik Zamenhof, who was born in Białystok in 1859. I imagined I was travelling back in time. Where did the name of this city come from and what was it like in the past? There is a 14th-century legend, that answers this question as it depicts Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas hunting aurochs in the wilderness: While the gunners were busy quartering the killed game, the prince rested by the stream. It was quite swift and, unlike other rivers and streams in this part of the forest, clear. This was probably because it had a sandy bottom and did not flow like other rivers among the peats[1]. He called it the White Slope [Biały Stok]. Formerly the word slope meant a stream or water that rolled downhill. However, it was not until the 16th century that a Gothic castle with a moat was built here, and later rebuilt in the Renaissance style. When it became the property of Marshal Jan Klemens Branicki in the 18th century, it was rebuilt in the Baroque style….

I look at the figure of a thoughtful boy – Zamenhof. His birth certificate, written in Russian and Hebrew, is in the State Archives in Białystok. In it one can read: Born according to the Christian calendar on December 3 and circumcised on December 10 [1859], according to the Jewish calendar, born on the 19th and circumcised on the 26th day of the month of kislev [5620] in Białystok. Data on parents: Mordka Felvelovich Zamenov, Liba Sholemovna Sofer. Name of the born child Leyzer[2]. We remember from the myth of Midas that the king touched his beloved daughter, who turned into a golden statue. Zamenhof standing on the sidewalk in Białystok is like a boy transformed into a statue. Where was he going at that moment when he suddenly became a statue? He was 13–14 years old at the time. His parents were already packing up their belongings and the family moved to Warsaw in 1873. Thus, only a personified memory remained in Białystok.

Recent research shows that Lejzer (who later changed his name to Ludwik) did not leave with his parents, but remained alone without their care to complete his education at the Białystok gymnasium. As Zbigniew Romaniuk writes: A teenager without the care of his immediate family, he lived in Białystok with his own affairs, not necessarily school affairs. Unfortunately, he flunked the first year, mainly due to reprehensible behavior. Repetition didn’t go his way from the start, and he eventually dropped out of the repeated first grade after less than two months. The director of the Białystok School Directorate expressed an opinion about Ludwig: “[…] not only did he eventually stop studying, but to the scorn of the students he ran away from class and wandered around the city during lessons […]”. Was he already thinking about creating a new language – Esperanto – during his truancy? Probably yes, since he wrote the drama “The Tower of Babel, or Białystok Tragedy in Five Acts” as early as 10 years old[3]. One language for people from all over the world was supposed to demolish the “Tower of Babel” once and for all. I studied Esperanto during my studies at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków and met individuals speaking this language in France.

Zamenhof also thought of creating a universal monotheistic religion, referring to the ancient scholar and religious leader Hillel. He called it Hillelism, and later homaranism (homaro means humanity in Esperanto). He dreamed that everyone around the world spoke the same language and followed the same religion, thus creating an ideal world where everyone would be brothers. From 1907 to 1917, he was nominated 8 times for the Nobel Peace Prize.

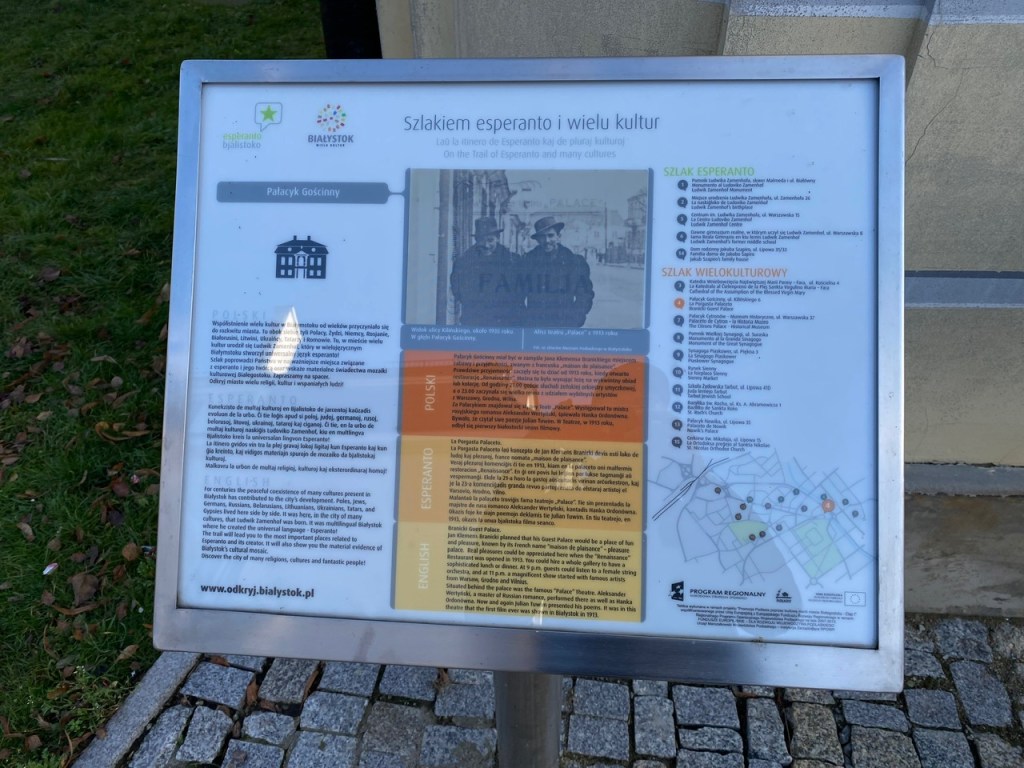

I abandoned the thoughtful Zamenhof and wandered towards the Branicki Palace. I passed the Guest Palace still, at which I found a plaque with information: The coexistence of many cultures in Białystok for centuries contributed to the flourishing of the city. Here Poles, Jews, Germans, Russians, Belarusians, Lithuanians, Ukrainians, Tatars and Roma lived side by side. Here in the city of many cultures was born Ludwik Zamenhof, who created the universal language Esperanto in multilingual Białystok! The Guest Palace, which now houses the Registry Office, was called a maison de plaisance (house of pleasure). Among other things, it hosted concerts by a female string orchestra and revues.

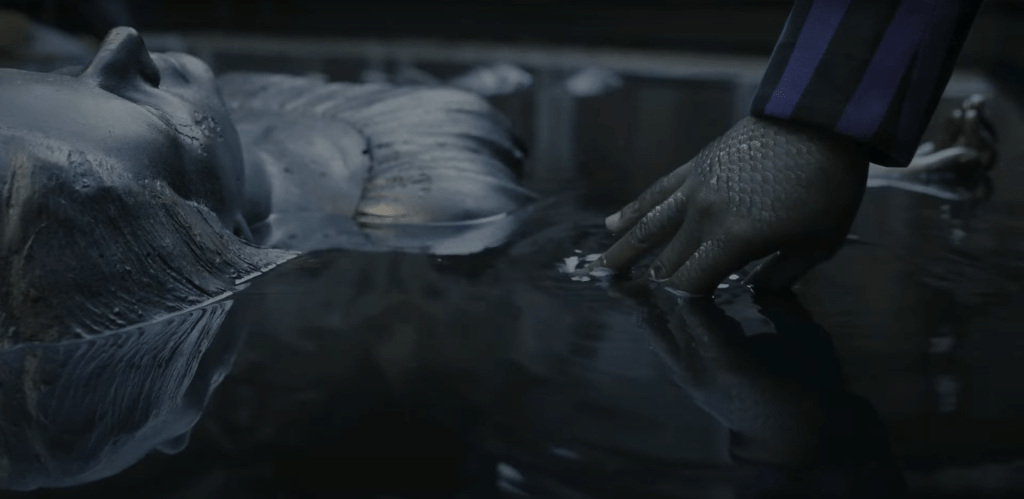

Finally, I entered through the beautiful Great Gate, with a clock and a sculpture of Griffin placed on it, into the courtyard of the Branicki Palace and garden establishment. I saw Atlas in the side wing, busy supporting the globe. As I climbed the stairs to the Palace, I saw several sculptures on the roof, among which Atlas was again towering, this time supporting a gilded globe, as if to illuminate the tympanum on which the coat of arms of the Branicki family – Gryf [Griffin] – was placed.

I headed to the interior of the Palace, where I was enchanted by the Great Vestibule, designed by architect Jakub Fontana. There are two entrances, one from the courtyard and the other from the gardens. The magnificent staircase structure is supported by two Atlantes, sculptures designed by Jan Chrysostom Redler. The same author also created the marble figure of a naked rotator – a grinder, placed at the beginning of the staircase. Many years ago, the rotator lost his head. In 1949, it was found in the attic of the High School of Fine Arts in Supraśl, near Białystok, by the school’s director Jan Chryzostom Redler. The Palace houses, among other things, the apartments of Izabela Branicka, the Great Hall, the Golden Rooms, and the study and dining room, where there is now a student reading room. The second floor windows offer a beautiful view of the gardens.

I went outside. The sunny weather made it a pleasure to walk around for an hour, admiring the sculptures of Greek gods and goddesses. According to Białystok University of Technology Professor Zygmunt Orłowski: the Palace was modelled on French spatial and decorative solutions. The result of these works was one of the most magnificent palaces and gardens in Europe, called by contemporaries “Versailles of Podlasie”. The gardens and animals stretched over an area of about 14 hectares, and in the 18th century the palace was mentioned as a rarity because there were more than 200 sculptures […]. During World War II, the garden was devastated and the palace burned down along with the interior and furnishings. It was reconstructed after the war[4].

For many years, art historian, priest Jan Nieciecki, has been engaged in the scientific study of the history of the Branicki Palace and garden establishment. He published his articles in the pages of the Conservator’s Bulletin of the Podlaskie Voivodeship, and also published a book Polish Versailles[5]. The seat of Jan Klemens Branicki was described in this way, and foreigners did so in the 18th century, including the famous German geographer Anton Friedrich Büsching, Ernst Ahasverus von Lehndorff, and William Coxe[6].

Art conservator Michał Jackowski, working on the reconstruction of the sculptures in the Branicki Gardens, compared them with those of France: At Versailles, the sculptures are made of white marble. Ours were made of sandstone and painted white. And now I understand what the purpose of this was. At Versailles, you can see the full effect – white sculptures against a background of greenery. There is full scenery, contrast, it looks simply beautiful. […] We had our own sandstone, so it was both cheaper and easier. Some sculptures (such as the vases that decorate the balustrade and elements of the gazebo) were made of wood and painted or whitewashed with lime. The sculptures in Branicki’s gardens were made by Jan Chryzostom Redler. […] Figures from Greek or Roman mythology were in fashion[7].

Walking through the garden, I looked at Diana (Artemis) and the nymph Kallisto, who were busy preparing for a hunt. In a moment, Actaeon may be turned into a deer and torn apart by his own dogs as punishment for peeping at Artemis and the nymphs in the bath. Apollo intends to devote himself to art and play the lyre. Venus (Aphrodite) may have just bathed in the river, and her lover Adonis shows how beautiful he is. Among the trees appear: Satyr (Pan) with horns, Bacchantes with a vine on her head, and proud Syrinx, who is about to turn into a reed as she runs away from Pan. I left the garden, passing by Sphinxes with Putti, who were looking at the beautiful sky with a smile, not paying me any attention. Gladiators with shields used to stand in this place, as if protecting the entrance and reminding me that there used to be a defensive castle here.

My uncle, Janusz Cezary Penderecki, talked about the beautiful Branicki Palace with enthusiasm. I thought of him while walking around the city. When he graduated from medical school in Białystok, he fulfilled one of his greatest dreams as an idealist – to help people. Later, he began practising medicine on ships, as he also dreamed of travelling. He sent us cards from North and South America. It was thanks to him that I started reading books by Verne, May, London, Malinowski…. He was killed in the Atlantic Ocean during the Falklands War. To this day, we have not learned what exactly happened there.

Such a time travel gives us the illusion of contact with the dead. When I was returning along the same road I came, I stopped again at the monument to Ludwig Zamenhof. I wanted to say to him: kiam mi estis studento, mi lernis Esperanton. I learned Esperanto when I was a student, but now English is like the Esperanto of our time. And what will happen in 20 years? Who knows? Soon we will probably be able to have instant simultaneous translation of all the world’s languages thanks to small devices at our ear. However, it is easier to travel to the past than to the future, because we have more tools to understand the essence of things. This is given to us by: history, philosophy, science, memories, experience, and myths. And also, traces left by those close to us.

Post by Krzysztof Korwin-Piotrowki, placed by Olga Strycharczyk

[1] Legendy województw: białostockiego, łomżyńskiego, suwalskiego, collected by Walentyna Niewińska, Wojewódzka Biblioteka Publiczna w Białymstoku, Białystok 1995, 10.

[2] Zbigniew Romaniuk, Ludwik Zamenhof – nieznane szczegóły białostockiego życiorysu, “Studia Podlaskie”, Białystok 2002, t. XII, 292.

[3] Ibidem, 298.

[4] Zygmunt Orłowski, Rekonstrukcja Bramy Wielkiej Pałacu Branickich w Białymstoku. Problemy wykonawcze, “Czasopismo Techniczne. Budownictwo” 2011, r. 108, z. 19, 3-B, 242.

[5] See: Jan Nieciecki, Polski Wersal, Białystok 1998.

[6] See: Jan Nieciecki, Opowieści o Polskim Wersalu, “Biuletyn Konserwatorski Województwa Białostockiego”, 1996, no. 2, 53.

[7] Katarzyna Malinowska-Olczyk, Detektyw w ogrodach, “Medyk Białostocki”, 28.06.2013, https://www.umb.edu.pl/medyk/polecane/detektyw_w_ogrodach (accessed 16.08.2023).

Białystok – podróż do przeszłości

Krzysztof Korwin-Piotrowski – reżyser teatralny i telewizyjny, doktorant i wykładowca na Wydziale “Artes Liberales” Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego. Od 2018 roku przewodniczy jury konkursu “Antyk – Kamera – Akcja!” skierowanego do licealistów, organizowanego w ramach projektu Our Mythical Childhood.

Kilka miesięcy temu po raz pierwszy w życiu pojechałem do Białegostoku, położonego na północnym wschodzie Polski, blisko granicy z Białorusią i niedaleko Litwy. Zostałem zaproszony na spektakle: Wokół Szekspira z jednym z najsłynniejszych polskich aktorów Andrzejem Sewerynem, w Nie Teatrze, oraz West Side Story, musical Leonarda Bernsteina w Operze i Filharmonii Podlaskiej. Oba przedstawienia były bardzo ciekawe, ale nie o nich chciałbym teraz opowiedzieć. Kiedy jestem w jakimś mieście pierwszy raz, lubię się trochę powłóczyć, aby odkryć je po swojemu, bez dokładnie wytyczonej trasy. Jednak moja mama Barbara Penderecka-Piotrowska przypomniała mi, że jej najstarszy brat mieszkał w Białymstoku przez kilka lat, studiując w Akademii Medycznej (obecnie Uniwersytecie Medycznym). Postanowiłem więc odnaleźć to miejsce, czyli Pałac Branickich.

Idąc od Rynku Kościuszki w kierunku pałacu, zobaczyłem niespodziewanie pomnik chłopca, trzymającego w lewej ręce książkę albo teczkę. Rzeźba została wykonana z mosiądzu. Okazało się, że to pomnik młodego Ludwika Zamenhofa, który urodził się w Białymstoku w 1859 roku. Wyobraziłem sobie, że podróżuję w czasie. Skąd pochodzi nazwa tego miasta i jakie było dawniej? Jest legenda o tym, że w XIV wieku Wielki Książę Litewski Giedymin polował w puszczy na tura: Podczas gdy strzelcy zajęci byli ćwiartowaniem ubitej zwierzyny, książę odpoczywał nad strumieniem. Był dosyć wartki i w przeciwieństwie do innych rzek i strumieni w tej części puszczy – czysty. Pewnie dlatego, że dno miał piaszczyste i nie płynął jak inne rzeki wśród torfów[1]. Nazwał go Białym Stokiem. Dawniej słowo stok oznaczało strumień czyli wodę, która staczała się w dół. Jednak dopiero w XVI wieku został tu wzniesiony gotycki zamek z fosą, przebudowany później w stylu renesansowym. Gdy stał się w VIII wieku własnością marszałka Jana Klemensa Branickiego, został przebudowany w stylu barokowym…

Spoglądam na postać zamyślonego chłopca – Zamenhofa. Jego akt urodzenia, napisany w języku rosyjskim i hebrajskim, znajduje się w Archiwum Państwowym w Białymstoku. Można w nim przeczytać: Urodzenie według kalendarza chrześcijańskiego 3, a obrzezanie 10 grudnia [1859 r.], według kalendarza żydowskiego urodzenie 19, a obrzezanie 26 dnia miesiąca kislew [5620 r.] w Białymstoku. Dane o rodzicach: Mordka Felwelowicz Zamenow, Liba Szolemowna Sofer. Imię narodzonego dziecka Lejzer[2]. Pamiętamy z mitu o Midasie, że król dotknął swoją ukochaną córkę, która zamieniła się w złoty posąg. Zamenhof stojący na chodniku w Białymstoku jest jak chłopiec przemieniony w statuę. Dokąd szedł w tym momencie, gdy nagle stał się pomnikiem? Miał wtedy 13–14 lat. Jego rodzice pakowali już swój dobytek i rodzina w 1873 roku przeniosła się do Warszawy. W Białymstoku pozostało więc tylko spersonifikowane wspomnienie.

Z ostatnich badań naukowych wynika, że Lejzer (który później zmienił imię na Ludwik) nie wyjechał z rodzicami, lecz pozostał sam bez ich opieki, aby dokończyć edukację w białostockim gimnazjum. Jak pisze Zbigniew Romaniuk: Nastolatek bez opieki najbliższej rodziny żył w Białymstoku własnymi, niekoniecznie szkolnymi sprawami. Niestety oblał pierwszy rok, głównie ze względu na naganne zachowanie. Repeta od początku mu nie szła i w końcu po niespełna dwóch miesiącach porzucił powtarzaną pierwszą klasę. Dyrektor Białostockiej Dyrekcji Szkół wyraził o Ludwiku opinię: „[…] nie tylko ostatecznie przestał się uczyć, ale ku zgorszeniu uczniów uciekał z klasy i w czasie lekcji włóczył się po mieście […]”. Czy podczas wagarów myślał już o tym, aby stworzyć nowy język – esperanto? Prawdopodobnie tak, skoro już jako 10-latek napisał dramat „Wieża Babel, czyli tragedia białostocka w pięciu aktach”[3]. Jeden język dla ludzi z całego świata miał zburzyć raz na zawsze „wieżę Babel”. Podczas studiów na Uniwersytecie Jagiellońskim w Krakowie chodziłem na lekcje esperanta i poznałem ludzi mówiących w tym języku podczas pobytu we Francji.

Zamenhof myślał też o tym, aby utworzyć uniwersalną religię monoteistyczną, odwołując się do starożytnego uczonego i przywódcy religijnego Hillela. Nazwał ją hilelizmem, a później homaranizmem (homaro to po esperancku ludzkość). Marzył więc o tym, aby wszyscy ludzie na całym świecie mówili tym samym językiem i byli wyznawcami jednej religii, co pozwoliłoby stworzyć idealny świat, w którym wszyscy będą braćmi. Od 1907 do 1917 roku był nominowany 8 razy do Pokojowej Nagrody Nobla.

Porzuciłem zamyślonego Zamenhofa i powędrowałem w kierunku pałacu Branickich. Minąłem jeszcze Pałacyk Gościnny, przy którym znalazłem tablicę z informacją: Współistnienie wielu kultur w Białymstoku od wieków przyczyniało się do rozkwitu miasta. Tu obok siebie żyli Polacy, Żydzi, Niemcy, Rosjanie, Białorusini, Litwini, Ukraińcy, Tatarzy i Romowie. Tu, w mieście wielu kultur urodził się Ludwik Zamenhof, który w wielojęzycznym Białymstoku stworzył uniwersalny język esperanto! Pałacyk Gościnny, w którym obecnie mieści się Urząd Stanu Cywilnego, był nazywany maison de plaisance (dom przyjemności). Odbywały się w nim między innymi koncerty żeńskiej orkiestry smyczkowej i rewie.

Wreszcie wszedłem piękną Bramą Wielką, z umieszczonym na niej zegarem i rzeźbą Gryfa, na dziedziniec założenia pałacowo-ogrodowego Branickich. Zobaczyłem w bocznym skrzydle Atlasa, zajętego podtrzymywaniem kuli ziemskiej. Gdy wchodziłem schodami do pałacu, ujrzałem na dachu kilka rzeźb, wśród których znowu górował Atlas, podtrzymujący tym razem pozłacaną kulę ziemską, jakby w ten sposób oświetlał tympanon, na którym umieszczony został herb Branickich – Gryf.

Skierowałem się do wnętrza pałacu, gdzie duże wrażenie wywarła na mnie Sień Wielka, zaprojektowana przez architekta Jakuba Fontanę. Wejście do niej jest z obu stron, od dziedzińca i ogrodów. Wspaniałą konstrukcję schodów podtrzymują dwaj Atlanci, rzeźby zaprojektowane przez Jana Chryzostoma Redlera. Ten sam autor stworzył również marmurową postać nagiego rotatora – szlifierza, umieszczoną na początku schodów. Wiele lat temu rotator stracił głowę. W 1949 roku odnalazł ją na strychu Liceum Sztuk Plastycznych w Supraślu, niedaleko Białegostoku, dyrektor szkoły Jan Chryzostom Redler. W pałacu znajdują się między innymi: apartamenty Izabeli Branickiej, Aula Wielka, Pokoje Złote oraz gabinet i jadalnia, gdzie obecnie jest czytelnia studencka. Z okien pierwszego piętra roztacza się piękny widok na ogrody.

Wyszedłem na zewnątrz. Słoneczna pogoda sprawiła, że z przyjemnością spacerowałem przez godzinę, podziwiając rzeźby greckich bogów i bogiń. Jak pisze prof. Politechniki Białostockiej Zygmunt Orłowski: Pałac wzorowano na francuskich rozwiązaniach przestrzennych i dekoracyjnych. W efekcie tych prac powstał jeden z najwspanialszych pałaców i ogrodów w Europie, nazwany przez współczesnych „Wersalem Podlaskim”. Ogrody i zwierzyńce rozciągały się na obszarze około 14 hektarów, a w XVIII w. pałac wymieniano jako ewenement, ponieważ było tu ponad 200 rzeźb […]. W czasie II wojny światowej ogród zdewastowano, a pałac spłonął wraz z wnętrzem i wyposażeniem. Po wojnie został zrekonstruowany[4].

Od wielu lat badaniem naukowym dziejów założenia pałacowo-ogrodowego Branickich zajmuje się historyk sztuki ks. Jan Nieciecki. Publikuje swoje artykuły na łamach Biuletynu Konserwatorskiego Województwa Podlaskiego, a także wydał książkę Polski Wersal[5]. W ten sposób określano siedzibę Jana Klemensa Branickiego, a czynili to w XVIII wieku obcokrajowcy, m.in. słynny niemiecki geograf Anton Friedrich Büsching, Ernst Ahasverus von Lehndorff czy William Coxe[6].

Konserwator dzieł sztuki Michał Jackowski, pracujący nad rekonstrukcją rzeźb w Ogrodach Branickich, porównywał je z francuskimi: W Wersalu rzeźby są zrobione z białego marmuru. U nas były wykonane z piaskowca i malowane na biało. I teraz już rozumiem, jaki był tego cel. W Wersalu widać pełen efekt – na tle zieleni białe rzeźby. Jest pełna scenografia, kontrast, wygląda to po prostu pięknie. […] Piaskowiec mieliśmy swój, więc było i taniej, i łatwiej. Niektóre rzeźby (np. wazy zdobiące balustradę i elementy altany) były robione z drewna i malowane lub bielone wapnem. Rzeźby w ogrodach Branickiego wykonał Jan Chryzostom Redler. […] W modzie były postacie z mitologii greckiej lub rzymskiej[7].

Spacerując po ogrodzie spoglądałem na Dianę (Artemidę) i nimfę Kallisto, które były zajęte przygotowaniami do polowania. Za chwilę Akteon może być zamieniony w jelenia i rozszarpany przez własne psy za karę, że podglądał Artemidę i nimfy w kąpieli. Apollo zamierza oddać się sztuce i grać na lirze. Wenus (Afrodyta) może przed chwilą kąpała się w rzece, a jej kochanek Adonis pokazuje, jaki jest piękny. Wśród drzew pojawiają się: Satyr (Pan) z rogami, Bachantka z winoroślą na głowie i dumna Syrinx, która zaraz może zamienić się w trzcinę, gdy będzie uciekać przez Panem. Wyszedłem z ogrodu, przechodząc obok Sfinksów z Puttami, które patrzyły z uśmiechem na piękne niebo, nie zwracając zupełnie na mnie uwagi. Kiedyś w tym miejscu stali Gladiatorzy z tarczami, jakby chronili wstępu i przypominali, że dawniej był tu zamek obronny.

Mój wujek Janusz Cezary Penderecki opowiadał o pięknym pałacu Branickich z entuzjazmem. Myślałem o nim, spacerując po mieście. Kiedy skończył studia medyczne w Białymstoku, spełnił jedno ze swoich największych marzeń. Był idealistą i chciał pomagać ludziom. Później zaczął pływać na statkach jako lekarz, ponieważ marzył także o podróżach. Wysyłał nam kartki z Ameryki Północnej i Południowej. Dzięki niemu zacząłem czytać książki Verne’a, Maya, Londona, Malinowskiego… Został zabity na Oceanie Atlantyckim w czasie wojny o Falklandy. Do dziś nie dowiedzieliśmy się, co dokładnie się tam wydarzyło.

Podróż w czasie daje nam złudzenie kontaktu ze zmarłymi. Kiedy wracałem tą samą drogą, którą przyszedłem, ponownie przystanąłem przy pomniku Ludwika Zamenhofa. Chciałem do niego powiedzieć: Kiam mi estis studento, mi lernis Esperanton. Uczyłem się esperanto, kiedy byłem studentem, ale teraz angielski jest jak esperanto naszych czasów. A co stanie się za dwadzieścia lat? Kto wie? Prawdopodobnie będziemy mogli już niedługo dzięki niewielkim urządzeniom przy uchu mieć błyskawiczne symultaniczne tłumaczenie wszystkich języków świata. Łatwiej jednak podróżować w przeszłość niż w przyszłość, ponieważ mamy więcej narzędzi do poznania istoty rzeczy. To dają nam: historia, filozofia, nauka, wspomnienia, doświadczenie i mity. A także ślady, pozostawione przez naszych bliskich.

Tekst przygotowany przez Krzysztofa Korwina-Piotrowskiego, zamieszczony przez Olgę Strycharczyk

[1] Legendy województw: białostockiego, łomżyńskiego, suwalskiego, zebrała Walentyna Niewińska, Wojewódzka Biblioteka Publiczna w Białymstoku, Białystok 1995, s. 10.

[2] Zbigniew Romaniuk, Ludwik Zamenhof – nieznane szczegóły białostockiego życiorysu, „Studia Podlaskie”, Białystok 2002, t. XII, s. 292.

[3] Tamże, s. 298.

[4] Zygmunt Orłowski, Rekonstrukcja Bramy Wielkiej Pałacu Branickich w Białymstoku. Problemy wykonawcze, „Czasopismo Techniczne. Budownictwo” 2011, r. 108, z 19, 3-B, s. 242.

[5] Por. Jan Nieciecki, Polski Wersal, Białystok 1998.

[6] Por. Jan Nieciecki, Opowieści o Polskim Wersalu, „Biuletyn Konserwatorski Województwa Białostockiego”, 1996, nr 2, s. 53.

[7] Katarzyna Malinowska-Olczyk, Detektyw w ogrodach, „Medyk Białostocki”, 28.06.2013, https://www.umb.edu.pl/medyk/polecane/detektyw_w_ogrodach (dostęp: 16.08.2023).