This post by Alexandria Kilmartin was written as an assignment for module Art & Life in the Ancient World, led by Dr Katerina Volioti, Lecturer in History at the University of Roehampton. Here you can find other posts prepared by the University of Roehampton international students:

– Ancient and Modern Entanglements: Roman Wall Paintings, by Rhianna Wallace,

– How Did Statues Change from the Archaic to the Classical Period?, by Lauren Husz,

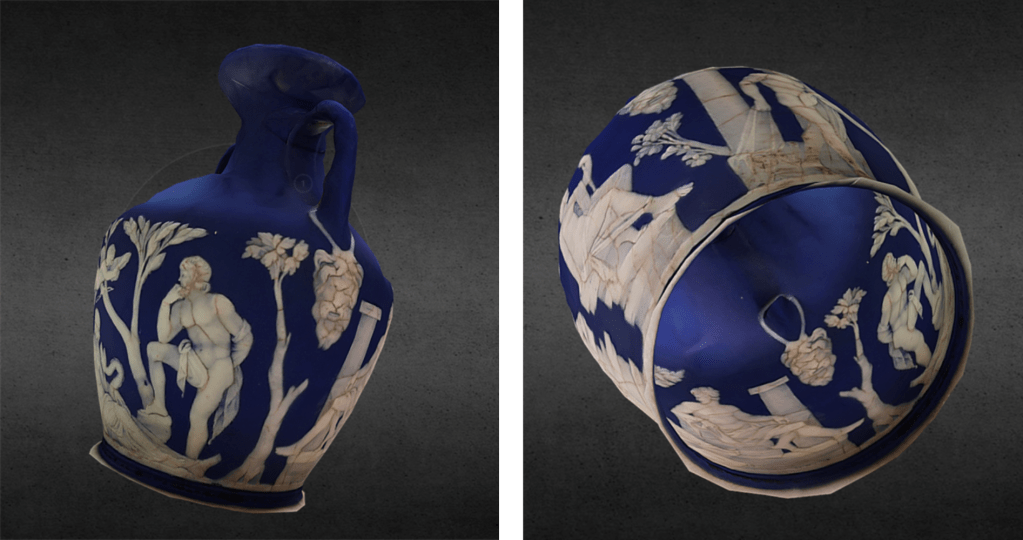

– The Portland Vase, by Rachel Rajmoney.

Acknowledgements

We are most grateful to Professor Katarzyna Marciniak and her team at the University of Warsaw for this opportunity to publish coursework by University of Roehampton Study Abroad. Below statement and essay by international student Alexandria Kilmartin who joined us at Roehampton all the way from Australia.

***

My name is Alexandria Kilmartin, but I go by Alex, and I am a study abroad student at the University of Roehampton. When not abroad, I study at Macquarie University, in Sydney, Australia, where I am completing a double degree of a Bachelor of Arts, majoring in Ancient History and a Bachelor of Linguistics and Language Sciences. I am a first-generation University student in my family and when I complete my undergraduate studies, I am aiming towards completing a masters in either speech pathology or furthering my historical research studies. Personally, and in my leisure time, I enjoy reading novels, I love the beach and going on long walks and getting coffees with my friends. I decided to select the Art & Life in the Ancient World course at Roehampton because I have always loved and appreciated art, and I was intrigued in developing deeper ideas surrounding art in Antiquity. The course connected with my purpose and decision to select the University of Roehampton and its specific location in proximity to the British Museum, as it has been a dream of mine to visit.

The Art & Life in the Ancient World module has significantly impacted how I view, interpret and interact with ancient art and has helped me develop ideas and evolve concepts in my academic work. Winklemann’s ideas originally interested me because of his perception of aesthetic and beauty standards. His ideas are incredibly evident in society today and, drawing from personal experiences as a young woman, I feel the connection between beauty and (face) value. Many ideas that are elaborated on in my essay I personally resonate with and that is why I was and am so passionate about this topic. I wanted to acknowledge that ideas of beauty are multifaceted and that beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Having the opportunity to be able to publish my work is an incredible opportunity and I am honoured to have been considered for this. I believe that this opportunity will significantly help my career in an overwhelmingly positive way and help me take a step closer to achieving my academic goals of completing a masters, furthering my education and deeper understanding of the world.

To what extent can we apply Winckelmann’s ideas about beauty to small and portable functional objects from Classical Antiquity? Discuss with reference to at least two objects.

Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768) has provided valuable ideas and perspectives on aesthetic, beauty, knowledge and understanding in his 1764 publication History of the Art of Antiquity (Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums, 1764).[1] Winckelmann has significantly contributed and inspired the classical archaeology discipline and study of neoclassical art. This essay will elaborate on how Winckelmann’s ideas about beauty can be successfully placed on humble, portable and functional objects. The pieces under discussion are a “Bronze Mirror with a support in the form of a draped woman” (mid-5th century BCE)[2] and secondly a “clay lekythos” (1st quarter of 5th century BCE) attributed to the Manner of the Haimon Painter.[3]

These functional objects are kept in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the study of these humble objects with reference to Winckelmann’s ideas can significantly contribute to an understanding of the importance of beauty juxtaposed to functionality, and if these concepts are exclusive. I will argue that Winckelmann’s ideas of subjective aesthetics can be used as a foundational assessment in attributing beauty and overall purpose. Specifically, that a more nuanced and less context-specific approach is required in assessing beauty and that functionality is more significant and equally as beautiful. There is scope for a more in-depth study of small finds in museum collections for a broader appreciation of ancient art and life.

Winckelmann is commonly attributed as “a source of inspiration for neo-classical art in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century” and is seen as the father of the classical archaeology discipline.[4] His History of the Art of Antiquity became a foundational text in neoclassical thought, shaping ideas about specific aesthetics and the idealized European body. Winckelmann believed that Greek art was the epitome of artistic creation and the experience of viewing it provoked joy. Based primarily on sculpture of the human physique, Winckelmann’s ideas are characterized by an unrealistic physical representation of the most elite and sophisticated Greek aesthetics. Winckelmann’s ideas assessed aesthetics in a philosophical and context specific manner that inspired subsequent generations of historians, artists and museum professionals. His publications encouraged enlightened intellectual inquiry on art history and philosophical aesthetics in eighteenth-century Germany. Classical scholar Katherine Harloe, for example, explores how Winckelmann’s ideas impacted German classicists from the 1840s.[5]

In my view, Winckelmann’s ideas provoke thoughtful discussions about ancient objects, their representations, and their surrounding context. The objects selected have been chosen because of their interaction with and representation of the human body, as well as their functional incorporation of movement. A key idea of Winckelmann’s “Rules of perspective” is that “[a]ll the arts have a double goal: they should give pleasure and at the same time instruct”.[6] This highlights that Winckelmann believed that something should be learnt from art. Thus, the objects under discussion are significant and I believe that the basic principles of Winckelmann’s ideas can be applied. Arguably, the rich historical, social and human interactions with functional material culture and the aesthetics of daily life are all ultimately beautiful and educational.

The first object under analysis is a finely crafted bronze mirror from the mid-5th century BCE (Figure 2). The mirror incorporates a statuette of a three-dimensional female figure as a base that supports the mirror. The design of a statuette figure in a functional object is a “hallmark of Greek art”[7], thus I believe that this particular representation of the human body would be an object that Winckelmann’s ideas can be applied to. The mirror features a collection of lively elements such as a human figure as well as animal and mythological creatures. Winged Erotes fly above the female statue’s head. Surrounding the mirrored disk are symmetrical pairs of hounds chasing hares, leading to the top of the mirror where a part bird, part woman siren is perched. Made out of a bronze, approximately 40,4 cm heigh and weighing 0,9 kg, the mirror was found in an Argive grave. The object relates to the human body by sensory, visual and physical touch experiences and displays visual aspects that reflect the classical period and context in which it was made.

The imagery and simplistic action of the woman ultimately holding up the mirrored disk contributes to a deeper metaphor and symbolism of beauty and connects to Winckelmann’s ideas about aesthetics. The stance and posture of the female statuette supports the mirror, simultaneously supporting the female or user of the mirror in their quest for beauty and their interaction with their appearance. “Her serious expression and quiet stance are typical of the retrained early Classical statues that were created from about 480 to 450 BC”, according to the MET online entry.[8] This mirror preserves and perpetuates symbolism of an idea of beauty that must be obtained, societal standards and epitome of beauty and self image. The entirety of the object includes symbolic motifs of beauty and subconscious undertones of elements of feminity. The object itself serves a functional purpose of providing a reflection. The statuette that supports the mirror is beautiful and delicate as it does reflect and reminds the viewer of monumental statues in stone, such as marble statues of Archaic korai dedicated on the Athenian Acropolis. Although the statuette aesthetically contributes to the overall beauty of the mirror, ultimately the most beautiful person is the user of the mirror and the human whose reflection is present. The functionality of the mirror provides a valuable and non-context specific idea of beauty that can be related to any human who uses the mirror.

The second object chosen for discussion in reference to Winckelmann’s ideas is a cursorily decorated oil flask, a lekythos from ca. 480 BCE (Figure 3). The lekythos depicts a four-horse chariot, a charioteer and a warrior. Originating from the late Archaic period the medium used is terracotta and the technique is black figure. This is a small container of oil that measures approximately 18 cm. The lekythos is connected to Athens’ international trade and to how “between ca. 500 to 450 BCE Mediterranean markets were flooded with low grade products in black figure”.[9] The lekythos depicts the Apobates Race, in which a fully armed warrior, the apobates, jumped off a four-horse chariot, ran alongside it, and mounted the charion again. The image is symbolic of athletic achievement and victory at the Panathenaia, Athens’ most celebrated religious festival. Thus, the iconography is connected with Winckelmann’s ideas about the human body and its capabilities. Unlike the finely crafted and detailed sculptures in which Winckelmann’s views are mostly applied to, the lekythos lacks detail and refinement in its decoration. Nonetheless, it depicts a most significant Athenian cultural event and that is what makes it culturally important and pleasing to the eye.

Although Winckelmann’s ideas may have only specifically been intended for sculpture and the human body, particular ideas about beauty can be reimagined also in the context of humble and everyday functional objects. Ultimately, these objects immortalize beauty and remind us that beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Aesthetically, the mirror statuette is more beautiful than the sketchy drawing on the oil flask. The human figures on the lekythos lack any anatomical details. Winckelmann does state that “[t]he most beautiful human body in our world would probably not resemble the most beautiful Greek body”[10] and argues that the idealistic bodies sculpted were acquired through their lifestyle. To me, this signals an elite culture of training in the gymnasium and enjoying healthy food ways. Both objects, the mirror and the lekythos, require functional and bodily interactions when placed in the hands of ancient participants. More importantly perhaps, both objects related to ancient beautification and body care. A woman presumably saw her reflection in the mirror. Another person probably used the olive oil in the lekythos to spice food and/or for skin care after exercising. The mirror signals a pleasing appearance where one acts and sculpts one’s appearance to fit the cultural context of beauty, presumably as in monumental religious objects such as the Acropolis korai. Similarly, the lekythos depicts a male in his prime physical fitness who is able to run besides horses. The lekythos also incorporates the action of achievement and greatness which embodies accomplishment, the human spirit and its idealism.

Winckelmann’s formulations encompass multiple imaginary ideas about perfection and the capabilities of the (male) human body. They may apply to a beautifully crafted mirror handle and a drawing of a warrior-athlete, even when both these representations of the human form are small scale and entangled with the function of their respective objects. Surely, Winckelmann’s ideas are rigid and context-specific. Nonetheless, they hold merit and can be applied to small and portable functional objects from ancient art and life. Although these objects are not grand and fine artistic creations, they represent how functionality and beauty need not be mutually exclusive. Winckelmann’s ideas can serve as a platform to nuance the study of daily-life objects from the ancient world, beyond monumental sculpture and architecture that tend to receive masses of scholarly attention.

[1] Johann Joachim Winckelmann, “History of the Art of Antiquity”, in: Johann Joachim Winckelmann and David Carter, Johann Joachim Winckelmann on Art, Architecture, and Archaeology, trans., introduction and notes by David Carter, Rochester (NY): Camden House, 2013, pp. 32–55, 127–128.

[2] “Bronze mirror with a support in the form of a draped woman”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/255391 (accessed 3 November 2025).

[3] “Lekythos”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/254397 (accessed 3 November 2025).

[4] Amy C. Smith, “Winckelmann, Greek Masterpieces, and Architectural Sculpture. Prolegomena to a History of Classical Archaeology in Museums”, in: Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja, eds., The Diversity of Classical Archaeology, “Studies in Classical Archaeology” 1, Turnhout: Brepols, 2017, pp. 1–33, via Central Archive at the University of Reading, https://centaur.reading.ac.uk/70169/1/Smith2018_preprint.pdf (accessed 3 November 2025).

[5] Eric M. Moormann, “[Review of] Winckelmann and Curiosity in the 18th-Century Gentleman’s Library: Christ Church Upper Library, 29 June – 26 October 2018 by Cristina Neagu, Katherine Harloe, and Amy Claire Smith”, Bryn Mawr Classical Review (2019) 2019.02.20, https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2019/2019.02.20 (accessed 3 November 2025).

[6] Johann Joachim Winckelmann, “History of the Art of Antiquity”.

[7] “Bronze mirror with a support in the form of a draped woman”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

[9] Jenifer Neils and Peter Schultz. “Erechtheus and the Apobates Race on the Parthenon Frieze (North XI–XII)”, American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 116, no. 2, 2012, pp. 195–200, DOI: 10.3764/aja.116.2.0195 (accessed 3 November 2025).

[10] Johann Joachim Winckelmann, “History of the Art of Antiquity”.

Bibliography

“Bronze mirror with a support in the form of a draped woman”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/255391 (accessed 3 November 2025).

“Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768)”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437067 (accessed 3 November 2025).

“Lekythos”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/254397 (accessed 3 November 2025).

Moormann, Eric M. “[Review of] Winckelmann and Curiosity in the 18th-Century Gentleman’s Library: Christ Church Upper Library, 29 June – 26 October 2018 by Cristina Neagu, Katherine Harloe, and Amy Claire Smith”, Bryn Mawr Classical Review (2019) 2019.02.20, https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2019/2019.02.20 (accessed 3 November 2025).

Neils, Jenifer and Peter Schultz. “Erechtheus and the Apobates Race on the Parthenon Frieze (North XI–XII)”, American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 116, no. 2, 2012, pp. 195–200, DOI: 10.3764/aja.116.2.0195 (accessed 3 November 2025).

Orrells, Daniel “[Review of] Winckelmann and the Invention of Antiquity: History and Aesthetics in the Age of Altertumswissenschaft. Classical presences by Katherine Harloe”, Bryn Mawr Classical Review (2014) 2014.12.06, https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2014/2014.12.06 (accessed 3 November 2025).

Smith, Amy C. “Winckelmann, Greek Masterpieces, and Architectural Sculpture. Prolegomena to a History of Classical Archaeology in Museums”, in: Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja, eds., The Diversity of Classical Archaeology, “Studies in Classical Archaeology” 1, Turnhout: Brepols, 2017, pp. 1–33, via Central Archive at the University of Reading, https://centaur.reading.ac.uk/70169/1/Smith2018_preprint.pdf (accessed 3 November 2025).

Winckelmann, Johann Joachim “History of the Art of Antiquity”, in: Johann Joachim Winckelmann and David Carter, Johann Joachim Winckelmann on Art, Architecture, and Archaeology, trans., introduction and notes by David Carter, Rochester (NY): Camden House, 2013, pp. 32–55, 127–128.

Post by Alexandria Kilmartin, prepared under tutorship by Dr Katerina Volioti, placed by Olga Strycharczyk