This post is an English updated version prepared by Wiktoria Popowicz’s (3rd year of Cultural Studies – Mediterranean Civilization) of her work for the classes “Ancient Greek Art around Us” conducted by Dr Alfred Twardecki at the Faculty of “Artes Liberales” UW in 2019/2020.

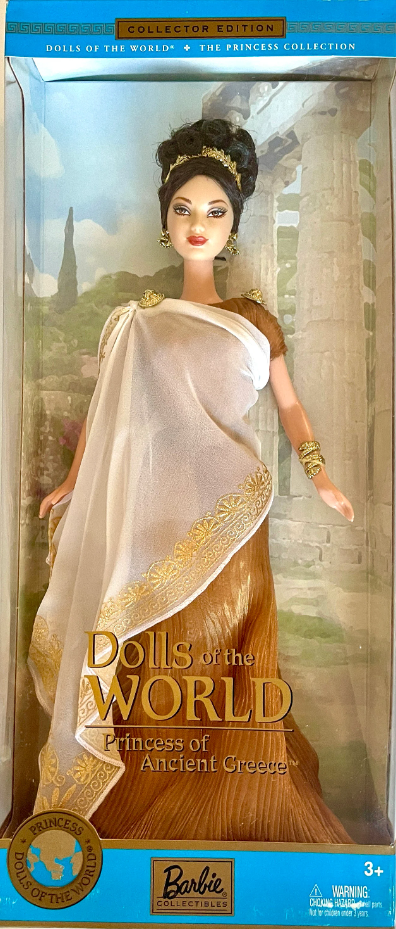

The echo of ancient Greek art returns and is still alive nowadays. Elements borrowed from the fragments of culture of the inhabitants of Hellas can be found in all areas. In 1980, the toy company Mattel produced a collector’s series of Barbie dolls “Dolls of the World – The Princess Collection”, which includes representatives of different countries and historical periods. The company has released 91 types of dolls in this series since then. Doll collectors receive a certificate and a passport confirming authenticity. Dolls’ distinguishing features are the costumes that characterize particular culture. Among them, the “Princess of Ancient Greece” from 2003 deserves attention, representing the ancient world that does not exist anymore:

The doll wears a dress stylized as a woman’s garment worn in ancient Greece. Since the original fabrics have not survived to our times, the designers of this toy could only use the available sources (including vase paintings and sculptures) supplemented with imagination.

The dress of the “Princess of Ancient Greece” consists of two elements: a golden-copper, shiny, free-flowing chiton and a white see-through scarf decorated with a golden pattern, called himation. It is tucked under the left shoulder and pinned on the right. You may compare Barbie’s dress with the one worn by Nike depicted in the red-figure oinochoe (illustration 1): the goddess wears a himation, from under which a chiton protrudes similar to the one in which the doll was dressed, made of pleated material that widens slightly at the feet.

The difference in the approach to ancient patterns is that the doll is made of plastic and synthetic materials, just like her clothes and jewelry. The colors – white and gold-copper metallic shade of the dress – may result from numerous stereotypical “naked” white sculptures devoid of old polychrome and poor colors conveyed by vase painting. The upper scarf is decorated with a golden floral pattern. Similar design motifs can also be found in vase painting. Two clips placed on the arms of the doll are also interesting. They imitate the golden brooches fastening the robe. They are shaped like lion heads. Similar representation can be found on the Greek pendant (illustration 2) and earrings (illustration 3).

Barbie’s “Princess of Ancient Greece” earrings also refer to the jewelry worn by the inhabitants of Hellas. They are large, golden, oval in shape. Archaeological excavations have provided many similar artifacts. The designers of the doll even took care of details such as the bracelet on the wrist. Analogous item (illustration 4) can be seen at the Metropolitan Museum of Arts in New York.

The clothes of the collectible dolls are very well made, but most often they cannot be taken off. The doll’s outfit is complemented by a plastic version of the golden tiara in the form of a laurel crown. Many real decorations have survived to our times (illustration 5), which could be an inspiration for artists.

In ancient Greece, wreaths were worn in religious ceremonies and were usually presented as prizes in sports and art competitions. The doll’s crown made of golden leaves is attached to lush, dark hair pinned up in a classic, high bun, reminiscent of the goddess Artemis’ hair in a red-figure vase (illustration 6).

The cardboard background behind the doll is also important. There are columns and construction elements suggesting the Doric style of the building. The time-gnawed marble is clearly visible. All this is surrounded by grass, empty spaces, and lush vegetation in the background. A similar sight can be seen, for example, in Athens and Paestum, where the preserved Doric temples are only a shadow, a remnant of the magnificent, colorful buildings from centuries ago, which the packaging designers did not take into account. Paradoxically, the doll was placed in a Greek landscape, but modern to us, full of ruins and white scattered marble. Contemporary reconstructions of Doric buildings (illustration 7) show what the architecture of ancient Greece is supposed to look like.

The designers probably referred to the image of the Acropolis that we know today (illustration 8), located in the capital of the country, making it the background.

The construction of the Barbie doll, especially the mobility of its joints, resembles the ancient Greek prototypes (illustration 9), whose arms and legs were connected to the body with a string or wire. The “Princess of Ancient Greece” shakes her head, can sit up, and move her legs and arms – similar to ancient Greek dolls, referred to as “neurospaston” (τὸ νευρόσπαστον, from: τὸ νεῦρον – “sinew, cord” and σπάω – “to draw”). Such Greek figurines were not always toys for children. They could have cult functions that would connect them to the adult world – much like the Barbie series of dolls intended for collectors.

Ancient Greek art surrounds us, but it is transformed, often difficult to see if we do not know what to look for. The background of the “Princess of Ancient Greece” doll is based on a schematic vision of Greece, with the ancient buildings turned into ruins, stripped of polychrome. It follows the stereotypical pattern, as does the doll’s outfit, which draws a lot from Greek fashion but modifies it quite freely. Nevertheless, some elements have a lot in common with reality, which is especially visible in the hairstyle and intricately made jewelry. Details such as a bracelet, a wreath, and brooches impress with their precision, despite their small size. “Princess of Ancient Greece” is an interesting and well-made example of the presence and use of ancient culture today.

Post written by Wiktoria Popowicz. We wish to ackowledge Dr Alfred Twardecki’s help in preparing the post and we also thank Dr Karolina Kulpa who specializes in Antiquity-inspired toys for her consultation.

Post elaborated by Dorota Rejter

Bibliography and Further Reading

- Bernhard Maria Ludwika: Ubiory starożytnej Grecji. Warszawa: Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie, 1956.

- Papuci-Władyka Ewdoksia: Sztuka starożytnej Grecji. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 2001.

- For more information about toys and games in Classical Antiquity, visit the website of the ERC Advanced Grant Project Locus Ludi led by Prof. Véronique Dasen at the University of Fribourg: https://locusludi.ch/.

- Currently, Prof. Dasen leads also the project focused on the ancient dolls, “Poupées articulées grecques et romaines” (see http://p3.snf.ch/project-192197).

Websites

- Amphora with the goddess Artemis on Theoi: https://www.theoi.com/Gallery/T14.4.html (accessed 4.12.2020).

- Ancient jewelry auctioned at Christie’s: https://www.christies.com/lot/lot-a-pair-of-greek-gold-double-lion-head-5004681 (accessed 29.12.2020); https://www.christies.com/lot/lot-a-greek-gold-myrtle-wreath-hellenistic-period-5547026/ (accessed 29.12.2020); https://www.christies.com/lot/lot-a-greek-gold-lion-head-pendant-classical-4396637 (accessed 29.12. 2020).

- Gold Greek Bracelet from The Metropolitan Museum of Art: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/255898 (accessed 4.12.2020).

- Greek clay doll from the Museum of Cycladic Art, Athens: https://cycladic.gr/en/exhibit/ng0142-plaggona-koukla?cat=archaia-elliniki-techni (accessed 30.12.2020).

- Kieran Orrell, A color reconstruction of the Parthenon, 2014: https://3dwarehouse.sketchup.com/model/9d37cd5ba5f94ef435e69d178ce2fc7a/The-Parthenon (accessed 4.12.2020).

- Parthenon from West, Wikimedia Commons: https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parthenon (accessed 13.01.2021).

- The Nikon Painter, Nike pursuing a bird, red-figured oinochoe, 470-450 BC, The British Museum (E538): https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1772-0320-220 (accessed 29.12.2020).-

- The official website of Barbie: https://barbie.mattel.com/shop/en-us/ba/collector-edition/princess-of-ancient-greece-barbie-doll-b3461 (accessed 4.12.2020).